Microservices in the Chronicle world – Part 1

At a high level, different Microservice strategies have a lot in common. They subscribe to the same ideals. When it comes to the details of how they are actually implemented, they can vary.

Microservices in the Chronicle world are designed around:

- Simplicity- simple is fast, flexable and easier to maintain.

- Transparency- you can’t control what you don’t understand.

- Reproduceablity- this must be in your design to ensure a quality solution.

What do we mean by simple?

A key part of the microservices design is how messages are passed between services/components. The simplest messages could be called asynchronous method calls.

An asynchronous method call is one which;

- doesn’t return anything,

- doesn’t alter it’s arguments;

- doesn’t throw any exceptions (although the underlying transport could).

The reason this approach is used, is that the simplest transport is no transport at all. One component calls another. This is not only fast ( and with inlining might not take any time at all), but it is simple to setup, debug and profile. For most unit tests you don’t need a real transport so there is no advantage in making the test more complicated than it needs to be.

Let’s look at an example.

Say we have a service/component which is taking incremental market data updates. In the simplest case, this could be a market update with only one side, a buy or a sell. The component could transform this into a full market update combining both the buy and sell price and quantity.

In this example, we have only one message type to start with, however we can add more message types. I suggest you create a different message name/method for each message rather than overloading a method.

Our inbound data structure

public class SidedPrice extends AbstractMarshallable {

final String symbol;

final long timestamp;

final Side side;

final double price, quantity;

public SidedPrice(String symbol, long timestamp, Side side, double price, double quantity) {

this.symbol = symbol;

this.timestamp = timestamp;

this.side = side;

this.price = price;

this.quantity = quantity;

}

}Our outbound data structure

public class TopOfBookPrice extends AbstractMarshallable {

final String symbol;

final long timestamp;

final double buyPrice, buyQuantity;

final double sellPrice, sellQuantity;

public TopOfBookPrice(String symbol, long timestamp, double buyPrice, double buyQuantity, double sellPrice, double sellQuantity) {

this.symbol = symbol;

this.timestamp = timestamp;

this.buyPrice = buyPrice;

this.buyQuantity = buyQuantity;

this.sellPrice = sellPrice;

this.sellQuantity = sellQuantity;

}

// more methods (1)

}For the complete code TopOfBookPrice.java

The component which takes one sided prices could have an interface;

Inbound interface for the first component

public interface SidedMarketDataListener {

void onSidedPrice(SidedPrice sidedPrice);

}and it’s output also has one method;

Outbound interface for the first component

public interface MarketDataListener {

void onTopOfBookPrice(TopOfBookPrice price);

}What does our microservice look like?

At a high level, the combiner is very simple;

public class SidedMarketDataCombiner implements SidedMarketDataListener {

final MarketDataListener mdListener;

final Map<String, TopOfBookPrice> priceMap = new TreeMap<>();

public SidedMarketDataCombiner(MarketDataListener mdListener) {

this.mdListener = mdListener;

}

public void onSidedPrice(SidedPrice sidedPrice) {

TopOfBookPrice price = priceMap.computeIfAbsent(sidedPrice.symbol, TopOfBookPrice::new);

if (price.combine(sidedPrice))

mdListener.onTopOfBookPrice(price);

}

}It implements our input interface and takes the output interface as a listener.

What does AbstractMarshallable provide?

The AbstractMarshallable class is a convenience class which implements toString(), equals(Object) and hashCode(). It also supports Marshallable’s writeMarshallable(WireOut) and readMarshallable(WireIn).

The default implementations use all the non-static non-transient fields to either print, compare or build a hashCode.

the resulting toString() can always be de-serialized with

Marshallable.fromString(CharSequence).Let’s look at a couple of examples.

SidedPrice sp = new SidedPrice("Symbol", 123456789000L, Side.Buy, 1.2345, 1_000_000);

assertEquals("!SidedPrice {\n" +

" symbol: Symbol,\n" +

" timestamp: 123456789000,\n" +

" side: Buy,\n" +

" price: 1.2345,\n" +

" quantity: 1000000.0\n" +

"}\n", sp.toString());

// from string

SidedPrice sp2 = Marshallable.fromString(sp.toString());

assertEquals(sp2, sp);

assertEquals(sp2.hashCode(), sp.hashCode());As you can see, the toString() is in YAML, concise, readable to a human and in code.

TopOfBookPrice tobp = new TopOfBookPrice("Symbol", 123456789000L, 1.2345, 1_000_000, 1.235, 2_000_000);

assertEquals("!TopOfBookPrice {\n" +

" symbol: Symbol,\n" +

" timestamp: 123456789000,\n" +

" buyPrice: 1.2345,\n" +

" buyQuantity: 1000000.0,\n" +

" sellPrice: 1.235,\n" +

" sellQuantity: 2000000.0\n" +

"}\n", tobp.toString());

// from string

TopOfBookPrice topb2 = Marshallable.fromString(tobp.toString());

assertEquals(topb2, tobp);

assertEquals(topb2.hashCode(), tobp.hashCode());

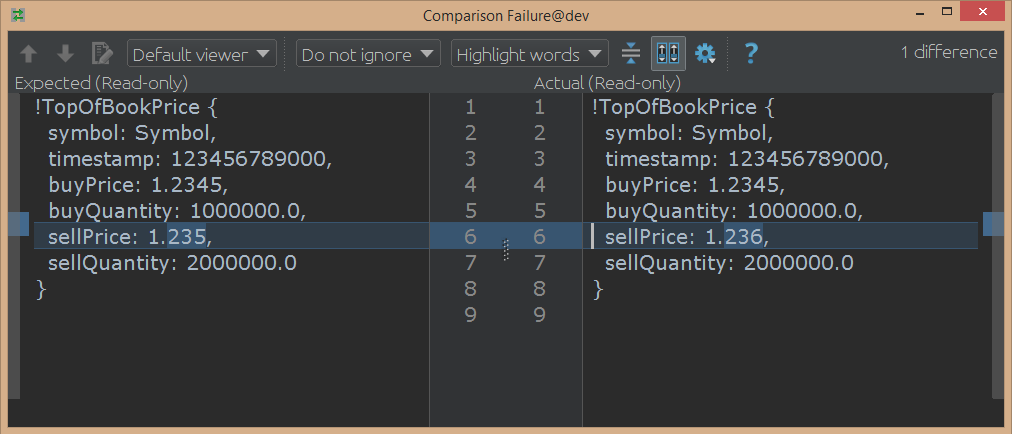

}One of the advantages of using this format is that it makes it easier to find the reason for a failing test even in complex objects.

Even in a trivial test it’s not obvious what the problem is

TopOfBookPrice tobp = new TopOfBookPrice("Symbol", 123456789000L, 1.2345, 1_000_000, 1.235, 2_000_000);

TopOfBookPrice tobp2 = new TopOfBookPrice("Symbol", 123456789000L, 1.2345, 1_000_000, 1.236, 2_000_000);

assertEquals(tobp, tobp2);However when you run this test in your IDE, you get a comparison window.

Figure 1. Comparison Windows in your IDE

If you have a large nested/complex object where assertEquals fails, it can really save you a lot of time finding what the discrepency is.

Mocking our component

We can mock an interface using a tool like EasyMock. I find EasyMock is simpler when dealing with event driven interfaces. It is not as powerful as PowerMock or Mockito, however if you are keeping things simple, you might not need those features.

// what we expect to happen

SidedPrice sp = new SidedPrice("Symbol", 123456789000L, Side.Buy, 1.2345, 1_000_000);

SidedMarketDataListener listener = createMock(SidedMarketDataListener.class);

listener.onSidedPrice(sp);

replay(listener);

// what happens

listener.onSidedPrice(sp);

// verify we got everything we expected.

verify(listener);We can also mock the expected output of a component the same way.

Testing our component

By mocking the output interface and calling the input interface for our compoonent we can check it behaves as expected.

MarketDataListener listener = createMock(MarketDataListener.class);

listener.onTopOfBookPrice(new TopOfBookPrice("EURUSD", 123456789000L, 1.1167, 1_000_000, Double.NaN, 0)); (1)

listener.onTopOfBookPrice(new TopOfBookPrice("EURUSD", 123456789100L, 1.1167, 1_000_000, 1.1172, 2_000_000)); (2)

replay(listener);

SidedMarketDataListener combiner = new SidedMarketDataCombiner(listener);

combiner.onSidedPrice(new SidedPrice("EURUSD", 123456789000L, Side.Buy, 1.1167, 1e6)); (1)

combiner.onSidedPrice(new SidedPrice("EURUSD", 123456789100L, Side.Sell, 1.1172, 2e6)); (2)

verify(listener);Setting the buy price Setting the sell price

Testing a series of components

Lets add an OrderManager as a down stream component. This order manager will receive both market data updates and order ideas, and in turn will produce orders.

// what we expect to happen

OrderListener listener = createMock(OrderListener.class);

listener.onOrder(new Order("EURUSD", Side.Buy, 1.1167, 1_000_000));

replay(listener);

// build our scenario

OrderManager orderManager = new OrderManager(listener); (2)

SidedMarketDataCombiner combiner = new SidedMarketDataCombiner(orderManager); (1)

// events in

orderManager.onOrderIdea(new OrderIdea("EURUSD", Side.Buy, 1.1180, 2e6)); // not expected to trigger

combiner.onSidedPrice(new SidedPrice("EURUSD", 123456789000L, Side.Sell, 1.1172, 2e6));

combiner.onSidedPrice(new SidedPrice("EURUSD", 123456789100L, Side.Buy, 1.1160, 2e6));

combiner.onSidedPrice(new SidedPrice("EURUSD", 123456789100L, Side.Buy, 1.1167, 2e6));

orderManager.onOrderIdea(new OrderIdea("EURUSD", Side.Buy, 1.1165, 1e6)); // expected to trigger

verify(listener);The first component combines sided prices The second component listens to order ideas and top of book market data

Debugging our components

You can see that one component just calls another. When debugging this single threaded code, each event from the first component is a call to the second component. When that finishes it returns to the first one and the tests.

When any individual event triggers an error, you can see in the stack trace which event caused the issue. However, if you are expecting an event which doesn’t happen, this is tricker unless your tests are simple (or you do a series of simple tests with verify(), reset() and replay().

it takes almost no time at all to start up the test and debug it in your IDE. You can run hundreds of tests like this in less than a second.

Source for examples

How do we create these as services?

We have shown how easy it is to test and debug our components. How do we turn these into services in Part 2.

| Reference: | Microservices in the Chronicle world – Part 1 from our JCG partner Peter Lawrey at the Vanilla Java blog. |