Git Tutorial – The Ultimate Guide (PDF Download)

Git is, without any doubt, the most popular version control system. Ironically, there are other version control systems easier to learn and to use, but, despite that, Git is the favorite option for developers, which is quite clarifying about the powerfulness of Git.

This guide will cover all the topics needed to know in order to use Git properly, from explaining what is it and how it differs from other tools, to its usage, covering also advanced topics and practices that can suppose an added value to the process of version controlling.

Table of contents

- 1. What is version control? What is Git?

- 2. Git vs SVN (DVCS vs CVCS)

- 3. Download and install Git

- 3.1. Linux

- 3.2. Windows

- 4. Git usage

- 4.1. Creating a repository

- 4.2. Creating the history: commits

- 4.3. Viewing the history

- 4.4. Independent development lines: branches

- 4.5. Combining histories: merging branches

- 4.6. Conflictive merges

- 4.7. Checking differences

- 4.8. Tagging important points

- 4.9. Undoing and deleting things

- 5. Branching strategies

- 5.1. Long running branches

- 5.2. One version, one branch

- 5.3. Regardless the branching strategy: one branch for each bug

- 6. Remote repositories

- 6.1. Writing changes in the remote

- 6.2. Cloning a repository

- 6.3. Updating remote references: fetching

- 6.4. Fetching and merging remotes at once: pulling

- 6.5. Conflicts updating remote repository

- 6.6. Deleting things in remote repository

- 7. Patches

- 7.1. Creating patches

- 7.2. Applying patches

- 8. Cherry picking

- 9. Hooks

- 9.1. Client-side hooks

- 9.2. Server-side hooks

- 9.3. Hooks are not included in the history

- 10. An approach to Continuous Integration

- 11. Conclusion

- 12. Resources

1. What is version control? What is Git?

Version control is the management of the changes made within a system, that it has not to be software necessarily.

Even if you have never used before Git or similar tools, you will probably have ever carried out a version control. A very used and bad practice in software developing is, when the software has reached a stable situation, saving a local copy of it, identifying it as stable, and then following with the changes in other copy.

This is something that every software engineer has done before using specific tools version controlling, so don’t feel bad if you have done it. Actually, this is much more better than having commented the code like:

/* First version

public void foo(int bar) {

return bar + 1;

}

*/

/* Second version

public void foo(int bar) {

return bar - 1;

}

*/

public void foo(int bar) {

return bar * 2;

}Which should be declared illegal.

The version control systems (VCS) are designed for carrying out a proper management of the changes. These tools provide the following features:

- Reversibility.

- Concurrency.

- Annotation.

The reversibility is the main capability of a VCS, allowing to return to any point of the history of the source code, for example, when a bug has been introduced and the code has to return to a stable point.

The concurrency allows to have several people making changes on the same project, facilitating the process of the integration of pieces of code developed by two or more developers.

The annotation is the feature that allows to add additional explanations and thoughts about the changes made, such us a resume of the changes made, the reason that has caused these changes, an overall description of the stability, etc.

With this, the VCSs solve one of the most common problems of software development: the fear for changing the software. You will be probably be familiar to the famous saying “if something works, don’t change it”. Which is almost a joke, but, actually, is like we act many times. A VCS will help you to get rid of being scared about changing your code.

There are several models for the version control systems. The one we mentioned, the manual process, can be considered as a local version control system, since the changes are only saved locally.

Git is a distributed version control system (DVCS), also known as decentralized. This means that every developer has a full copy of the repository, which is hosted in the cloud.

We will see more in detail the features of DVCSs in the following chapter.

2. Git vs SVN (DVCS vs CVCS)

Before the DVCSs burst into the version controlling world, the most popular VCS was, probably Apache Subversion (known also as SVN). This VCS was centralized (CVCS). A centralized VCS is a system designed to have a single full copy of the repository, hosted in some server, where the developers save the changes they made.

Of course, using a CVCS is better than having a local version control, which is incompatible with teamwork. But having a version control system that completely depends on a centralized server has an obvious implication: if the server, or the connection to it goes down, the developers won’t be able to save the changes. Or even worse, if the central repository gets corrupted, and no backup exists, the history of the repository will be lost.

CVCSs can also be slow. Recording a change in the repository means making effective the change in the remote repository, so, it relies on the connection speed to the server.

Returning to Git and DVCSs, with it, every developer has the full repository locally. So, the developers can save the changes whenever they want. If at certain moment the server hosting the repository is down, the developers can continue working without any problem. And the changes could be recorded into the shared repository later.

Another difference with CVCSs, is that DVCSs, specially Git, are much more faster, since the changes are made locally, and the disk access is faster than network access, at least in normal situation.

The differences between both systems could be summed up to the following: with a CVCS you are enforced to have a complete dependency on a remote server to carry out your version control, whereas with a DVCS the remote server is just an option to share the changes.

You may skip installation and jump directly to the beginning of the guide below.

3. Download and install Git

3.1. Linux

As you probably have guessed, Git can be installed in Linux executing the following commands:

sudo apt-get update sudo apt-get install git

3.2. Windows

Firstly, we have to download the last stable release from official page.

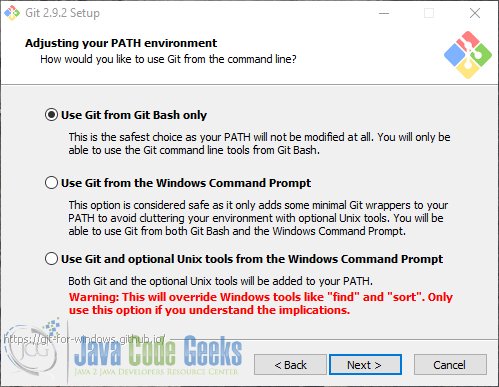

Run the executable, and click “next” button until you get to the following step:

Check the first option. The following options can be left as they come by default. You are about four or five “next” ago of having Git installed.

Now, if you open the context menu (right click), you will see two new options:

- “Git GUI here”.

- “Git Bash here”.

In this guide we will be using the bash. All the commands shown will be for their execution in this bash.

4. Git usage

In this chapter, we will see how to use Git to start with our version controlling.

4.1. Creating a repository

To begin using Git, we have first to create a repository, also known as “repo”. For that, in the directory where we want to have the repository, we have to execute:

git init

We have a Git repository! Note that a folder named .git has been created. The repository will be the directory where the .git folder is placed. This folder is the repository metadata, an embedded database. It’s better not to touch anything inside it while you are not familiarized with Git.

4.2. Creating the history: commits

Git constructs the history of the repository with commits. A commit is a full snapshot of the repository, that is saved in the database. Every state of the files that are committed, will be recoverable later at any moment.

When doing a commit, we have to choose which files are going to be committed; not all the repository has to be committed necessarily. This process is called staging, where files are added to the index. The Git index is where the data that is going to be saved in the commit is stored temporarily, until the commit is done.

Let’s see how it works.

We are going to create a file and add some content to it, for example:

echo 'My first commit!' > README.txt

Adding this file, the status of the repository has changed, since a new file has been created in the working directory. We can check for the status of the repository with the status option:

git status

Which, in this case, would generate the following output:

On branch master Initial commit Untracked files: (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed) README.txt nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

What Git is saying is “you have a new file in the repository directory, but this file is not yet selected to be committed“.

If we want to include this file the commit, remember that it has to be added to the index. This is made with the add command, as Git suggests in the output of status :

git add README.txt

Again, the status of the repository has changes:

On branch master Initial commit Changes to be committed: (use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage) new file: README.txt

Now, we can do the commit!

git commit

Now, the default text editor will be shown, where we have to type the commit message, and then save. If we leave the message empty, the commit will be aborted.

Additionally, we can use the shorthand version with -m flag, specifying the commit message inline:

git commit -m 'Commit message for first commit!'

We can add all the files of the current directory, recursively, to the index, with .:

git add .

Note that the following:

echo 'Second commit!' > README.txt git add README.txt echo 'Or is it the third?' > README.txt git commit -m 'Another commit'

Would commit the file with 'Second commit!' content, because it was the one added to the index, and then we changed the file of the working directory, not the one added to staging area. To commit the latest change, we would have to add again the file to the index, being the first added file overwritten.

Git identifies each commit uniquely using SHA1 hash function, based on the contents of the committed files. So, each commit is identified with a 40 character-long hexadecimal string, like the following, for example: de5aeb426b3773ee3f1f25a85f471750d127edfe. Take into account that the commit message, commit date, or any other variable rather than the committed files’ content (and size), are not included in the hash calculation.

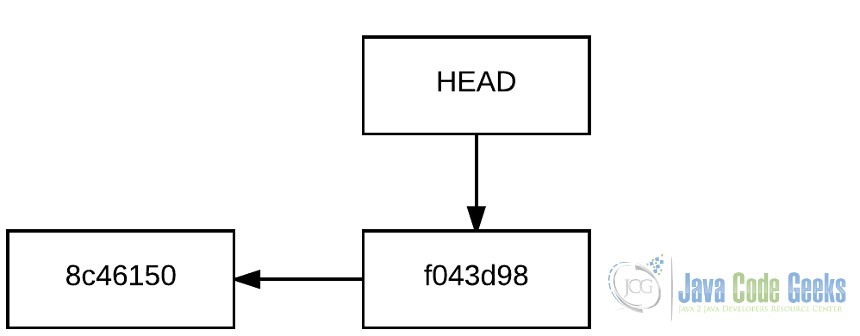

So, for our first two commit, the history would be the following:

Git shortens the checksum of each commit to 7 characters (whenever it’s possible), to make them more legible.

Each commit points to the commit it has been created from, being this called the “ancestor”.

Note that HEAD element. This is one of the most important element in Git. The HEAD is the element that points to the current point in the repository history. The contents of the working directory will be those that belong to the snapshot the HEAD is pointing to.

We will see this HEAD more in detail later.

4.2.1. Tips for creating good commit messages

The commit message content is more important that it may seem at first sight. Git allows to add any kind of explanation for any change we made, without touching the source code, and we should always take advantage of this.

For the message formatting, there’s an unwritten rule known as the 50/72 rule, which is so simple:

- One first line with a summary of no more than 50 characters.

- Wrap the subsequent explanations in lines of no more than 72 characters.

This is based on how Git formats the output when we are reviewing the history.

But, more important than this, is the content of the message itself. The first thing that comes to mind to write are the changes that have been made, which is not bad at all. But the commit object itself is a description of the changes that have been made in the source code. To make the commit messages useful, you should always include the reason that motivated the changes.

4.3. Viewing the history

Of course, Git is able to show the history of the repository. For that, the log command is used:

git log

If you try it, you will see that the output is not very nice. The log command has many flags available to draw pretty graphs. Here’s a suggestion for using this command through this guide, even if graphs are shown for each scenario:

git log --all --graph --decorate --oneline

If you want, you can omit the --oneline flag for showing the full information of each commit.

4.4. Independent development lines: branches

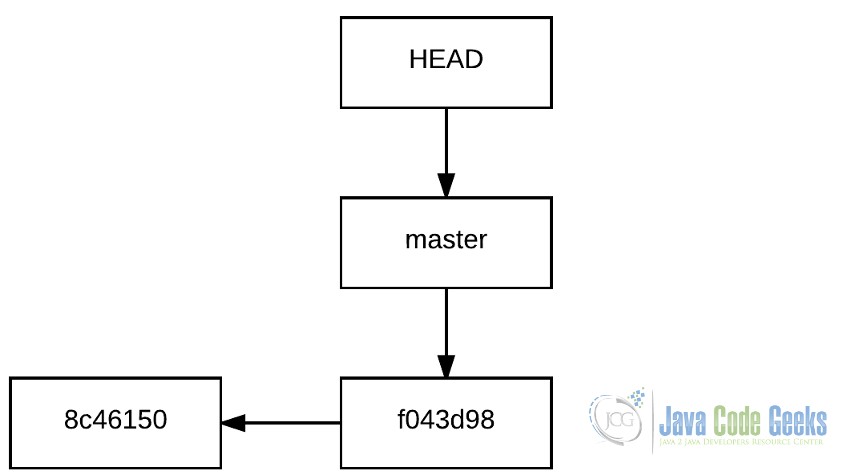

Branching is probably the most powerful feature of Git. A branch represents an independent development path. The branches coexist in the same repository, but each one has its own history. In the previous section, we have worked with a branch, Git’s default branch, which is named master.

Taking into account this, the proper way to express the history would be the following, considering the branches.

Creating a branch with Git is so simple:

git branch <branch-name>

For example:

git branch second-branch

And that’s it.

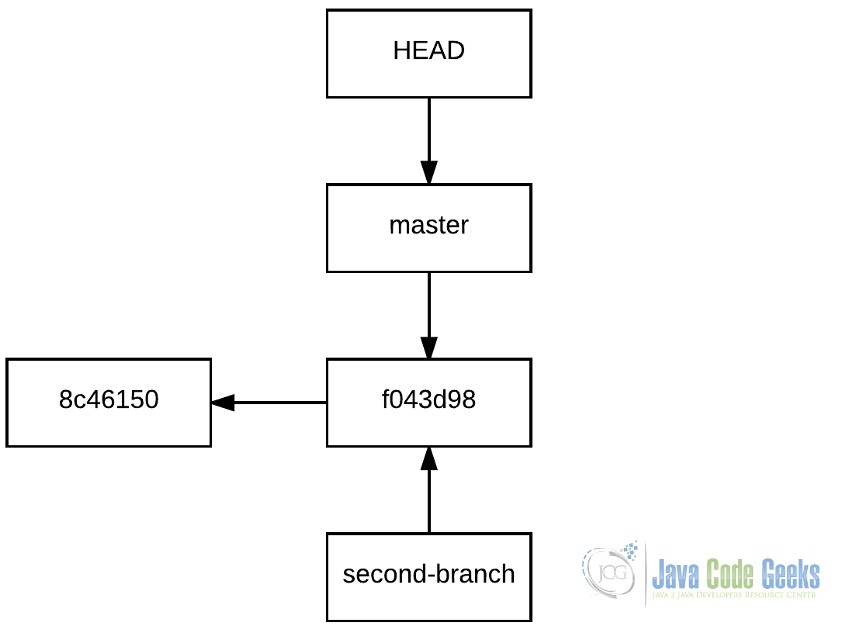

But, what is Git doing really when it creates a branch? It just creates a pointer with that branch name that points to the commit where the branch has been created:

This is one of the most notable features of Git: the branch creation speed, almost instantaneous, regardless of the repository size.

To start working in that branch, we have to checkout it:

git checkout second-branch

Now, the commits will only exist in second-branch. Why? Because the HEAD now is pointing to second-branch, so, the history created from now will have an independent path from master.

We can see it making a couple of commits being located in second-branch:

echo 'The changes made in this branch...' >> README.txt git add README.txt git commit -m 'Start changes in second-branch' echo '... Only exist in this branch' >> README.txt git add README.txt git commit -m 'End changes in second-branch'

If we check for the content of the file we have being modifying, we will see the following:

Second commit! The changes made in this branch... ... Only exist in this branch

But, what if we return to master?

git checkout master

The content of the file will be:

Second commit!

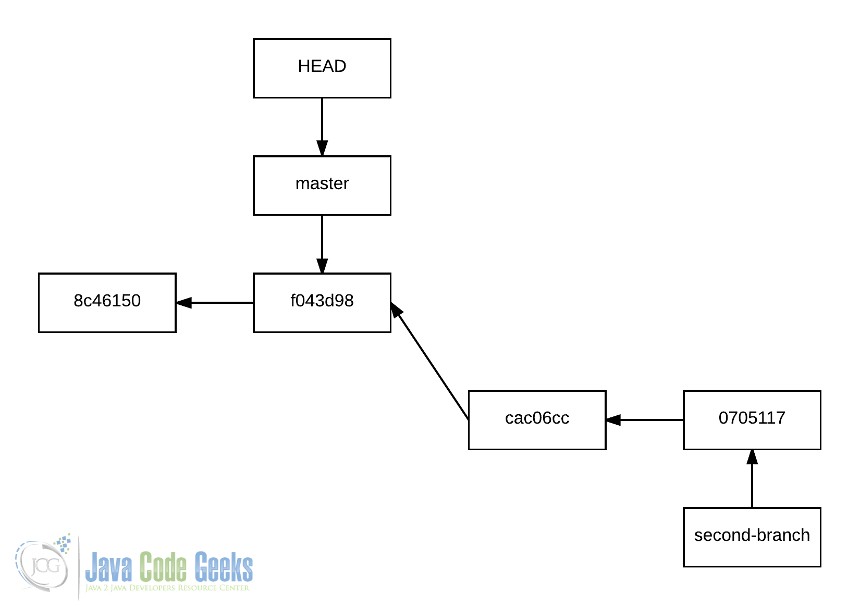

This is because, after creating the history of second-branch, we have placed the HEAD pointing to master:

4.5. Combining histories: merging branches

In the previous subsection, we have seen how we can create different paths for our repository history. Now, we are going to see how to combine them, what for Git is calling merging.

Let’s suppose that, after the changes made in second-branch, is ready to return to master. For that, we have to place the HEAD in the destination branch (master), and specify the branch that is going to be merged to this destination branch (second-branch), with merge command:

git checkout master git merge second-branch

And Git will give the following output:

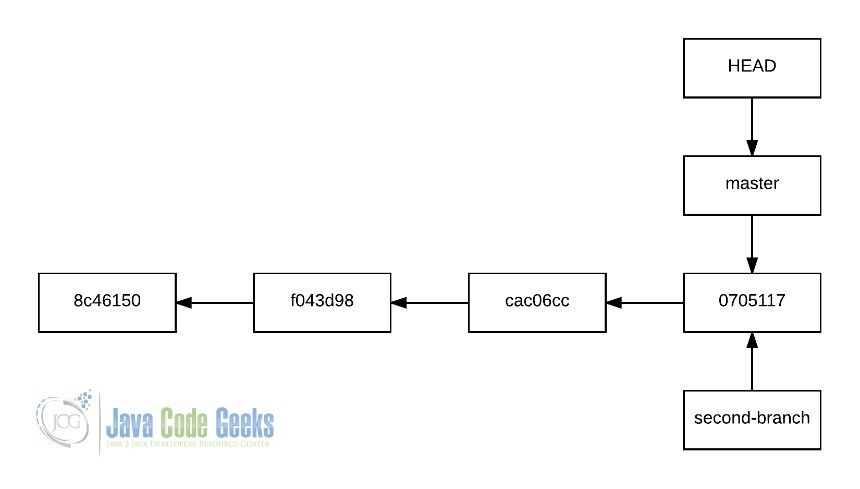

Updating f043d98..0705117 Fast-forward README.txt | 2 ++ 1 file changed, 2 insertions(+)

Now, the history of the second-branch has been merged to master, so, all the changes made in this first branch have been applied to the second.

In this case, the entire history of second-branch is now part of the history of master, having a graph like the following:

As you can see, no track of the life of second-branch has been saved, when you probably were expecting a nice tree.

This is because Git merged the branch using the fast-forward mode. Note that is telling it in the merge output, shown above. Why did Git do this? Because master and second-branch shared the common ancestor, f043d98.

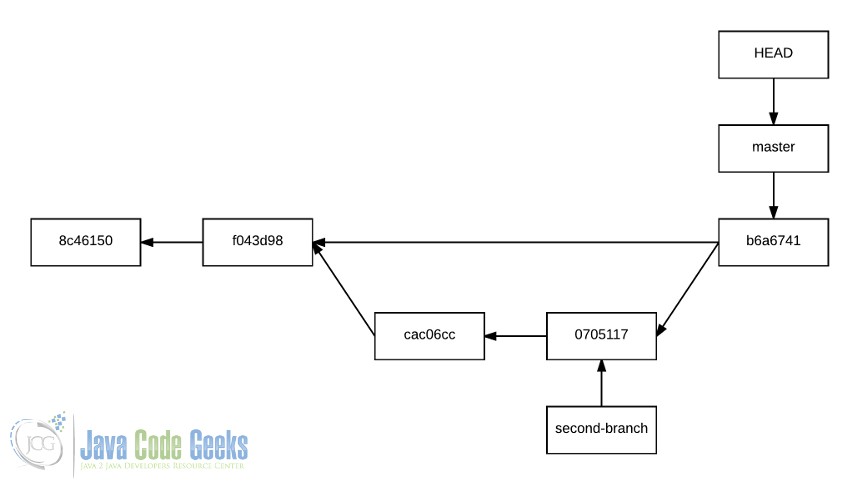

When we are merging branches, is always advisable not to use the fast-forward mode. This is achieved passing --no-ff flag while merging:

git merge --no-ff second-branch

What does this really do? Well, it just creates an intermediate, third commit, between the HEAD, and the “from” branch’s last commit.

After saving the commit message (of course, is editable), the branch will be merged, having the following history:

Which is much more expressive, since the history is reflected as it is actually is. The no fast-forward mode should be always used.

A merge of a branch supposes the end of the life of this. So, it should be deleted:

git branch -d second-branch

Of course, in the future, you can create again a second-branch named branch.

4.6. Conflictive merges

In the previous section we have seen an “automatic” merge, i.e., Git has been able to merge both histories. Why? Because of the previously mentioned common ancestor. That is, the branch is returning to the point it started from.

But, when the branch another branch borns from suffers changes, problems appear.

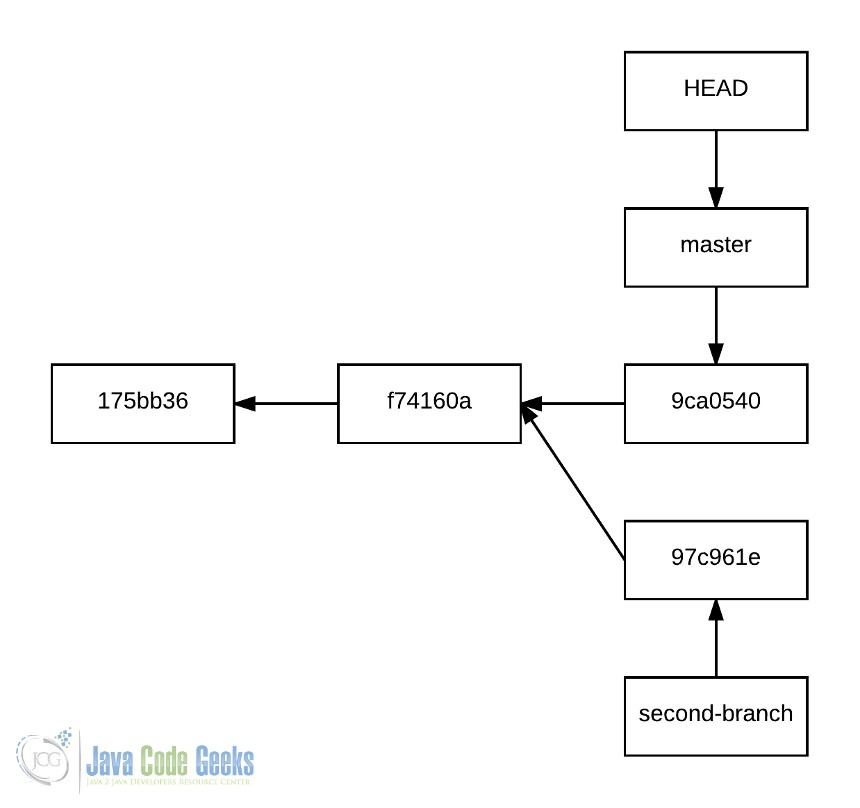

To understand this, let’s construct a new history, which will have the following graph:

With the following commands:

echo 'one' >> file.txt git add file.txt git commit -m 'first' echo 'two' >> file.txt git add file.txt git commit -m 'second' git checkout -b second-branch echo 'three (from second-branch)' >> file.txt git add file.txt git commit -m 'third from second branch' git checkout master echo 'three' >> file.txt git add file.txt git commit -m 'third'

What will happen if we try to merge second-branch to master?

git checkout master git merge second-branch

Git won’t be able to do it:

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in file.txt Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

Git doesn’t know how to do it, because the changes made in second-branch are not directly applicable to master, since it has changed from this first branch inception. What Git has done is to indicate in which parts exists these incompatibilities.

Note that we haven’t used the --no-ff flag, since we now in advance that the fast-forward won’t be possible.

If we check the status, we will see the following:

On branch master You have unmerged paths. (fix conflicts and run "git commit") Unmerged paths: (use "git add <file>..." to mark resolution) both modified: file.txt

Showing the conflictive files. If we open it, we will see that Git has added some strange lines:

one two <<<<<<< HEAD three ======= three (from second-branch) >>>>>>> second-branch

Git has indicated which are the incompatible changes. And how does it know? The incompatible changes are those that have been introduced into the “to” merging branch (master) since the creation of the “from” merging branch (second-branch).

Now, we have to decide how to combine the changes. On the one hand, the changes introduced to the current HEAD are shown (between <<<<<<< HEAD and =======), and, on the other, the branch we are trying to merge (between ======= and >>>>>>> second-branch). To solve the conflict, there are three options:

- Use

HEADversion. - Use

second-branchversion. - A combination of two versions.

Regardless the option, the file should end without any of the metacharacters that Git has added to identify the conflicts.

Once the conflicts have been resolved, we have to add the file to the index and continue with the merge, with commit command:

git add file.txt git commit

Once saved the commit, the merge will be done, having Git created a third commit for this merge, as with when we used the --no-ff in the previous section.

4.6.1. Knowing in advance which version to stay with

It may happen that we know beforehand which version we want to choose in case of conflicts. In these cases, we can tell Git which version use, to make it apply it directly.

To do this, we have to pass the -X option to merge, indicating which version use:

git merge -X <ours|theirs> <branch-name>

So, for using HEAD version, we would have to use ours option; instead, for using the version that is not HEAD‘s, theirs has to be passed.

That is, the following:

git merge -X ours second-branch

Would leave the file as is shown:

one two three

And, the following:

git merge -X theirs second-branch

As it follows:

one two three (from second-branch)

4.7. Checking differences

Git allows to check the differences between distinct points in the history. This is done with diff option.

4.7.1. Interpreting the differences

Before seeing what differences we can look at, firstly we have to understand how the differences are shown.

Let’s see a sample output of a difference between the same file:

diff --git a/README.txt b/README.txt index 31325b6..55e8d58 100644 --- a/README.txt +++ b/README.txt @@ -1,2 +1,2 @@ -This is -the original file +This file +has been modified

Here, a is the a previous version of the file, and b the current version.

The third and fourth line identifies each letter with a - or + symbol.

That @@ -1,2 +1,2 @@ is called “hunk header”. This identifies the chunks of code that actually have changed, not showing the common parts for both versions.

The format is the following:

@@ <previous><from-line>,<number-of-lines> <current>,<from-line><number-of-lines>

In this case:

- “previous”: identified with

-, corresponding toa. - “from-line”: the line number from where the changes start.

- “number-of-lines”: the number of lines shown.

- “current”: identified with

+, corresponding tob.

Finally, which lines are subtracted, and which added, are shown. In this case, two lines have been subtracted from the line (those preceded with -), and other two have been added (preceded with +).

4.7.2. Differences between working directory and last commit

One common use is to check the differences between the working directory and the last commit. For this, is enough to execute:

git diff

Which will show the difference for every file. We can specify also specific files:

git diff <file1> <file2>

4.7.3. Differences between exact points in history

We can look for differences with:

- SHA1 id

- Branch names

HEAD- Tags

Being combinable between them.

The syntax is the following:

git diff <original>..<modified>

For example, the following would show the changes that have been applied to dev branch, compared to a v1.0 tag:

git diff v1.0..dev

4.8. Tagging important points

Tagging is one of the nicest features of Git, since allows to mark important points in the repository history, in a very easy way. Usually, tags are used to mark releases, not only for stable releases, but also for under-development or incomplete releases, such as:

- Alpha

- Beta

- Release candidate (rc)

Creating a tag is so simple, we just have to situate the HEAD in the point we want to tag, and just specify the tag name with the tag option:

git tag -a <tag-name>

For example:

git tag -a v0.1-beta1

Then, we will be asked to type a message for the tag. Typically, the changes made from last tag are specified.

As when committing, we can specify the tag message inline, with -m flag:

git tag -a v0.1 -m 'v0.1 stable release, changes from...'

Take into account that the tag names cannot be repeated in a repository.

4.9. Undoing and deleting things

Git also allows to undo and modify some things in the history. In this section we will see what can be done, and how.

4.9.1. Modifying the last commit

Is quite common to want to modify the last commit, for example, when just a line of code has to be added; or even to modify the update message, without changing any file.

For that, Git has the --amend flag for commit command:

git commit --amend

This is just the same as committing, but, instead of a new commit object, the last one of that branch will be overwritten.

4.9.2. Discarding uncommitted changes

This is for, after a commit, when we keep developing, we think that we have taken an incorrect path, and we want to reset the changes, returning to the last commit’s state.

For this, the command used is checkout, as for moving between branches. But, when specifying a file, this gets reseted to the state of the last commit.

For example:

echo 'one' > test.txt git add test.txt git commit -m 'commit one' echo 'two' > test.txt git checkout test.txt # The content of test.txt is now 'one'.

4.9.3. Deleting commits

Usually, we want to delete commits when we don’t want to leave any record of an embarrassing commit, or just for removing useless changes.

This is achieved moving the branch or HEAD pointers. Moving the pointers to previous commits makes the commits remaining ahead get “lost”, unlinked from the linked list. To move them, reset command is used.

There are two ways of making a reset: not touching the working directory (soft reset, --soft flag), or resetting it too (hard reset, --hard flag). That is, if you make a soft reset, the commit(s) will be removed, but the modifications saved in that/those commit(s) will remain; and a hard reset, won’t leave change made in the commit(s). If no flag is specified, the reset will be done softly.

Let’s start resetting things. The following command would remove the last commit, i.e., the commit where HEAD is pointing to:

git reset --hard HEAD~

The ~ character is for indicating an ancestor. Used once, indicates the immediate parent; twice, the grandparent; and so on. But, instead of typing ~ n times, we can specify the n ancestors that we want to remove:

git reset --hard HEAD~3

Which would remove the last 3 commits.

You may have noticed that this may cause conflicts with those commits with more than one ancestor, i.e., the result of a not fast-forwarded merge. Well, it doesn’t cause any problem: the followed parent using HEAD~ is always the first one. But there’s a way to decide which of the common parents follow: ^, followed by the parent number. So, the following:

git reset --hard HEAD~2^2

Would remove the previous two commits, but taking the path of the second ancestor.

Even if it is possible to specify which ancestor path follow, is recommended to always use the syntax for first ancestor (only ~) since it’s easier, even if more commands would be required (since you would have to checkout the different branches to update HEAD position).

4.9.4. Deleting tags

Deleting tags is so simple:

git tag -d <tag-name>

5. Branching strategies

Reached this point, you may have already asked your self: “Okay, branches are cool, but when should I create and merge them?”

When we want to carry out a version control, we need to know which strategy we are going to follow. Using Git without having a clear branching policy is a complete nonsense.

The branching workflow to follow depends, mainly, on how we want to maintain the code. In this section, we will see the two main branching strategies.

5.1. Long running branches

This strategy is used when we want to maintain a single version of our software at the same time. That is, when we offer the last version of our software as available, instead of having many versions (which can be still available, but considered as old or unmaintained).

The key of this strategy is having a branch only for stable versions, where the releases are tagged, for which the default branch is used, master; and having other branches for development, where the features are developed, tested, and integrated.

In this strategy, the master branch is the production branch, so only tested, properly integrated, definitive versions should be here. Or, there can also be under-development or not fully tested versions, but they must be properly tagged.

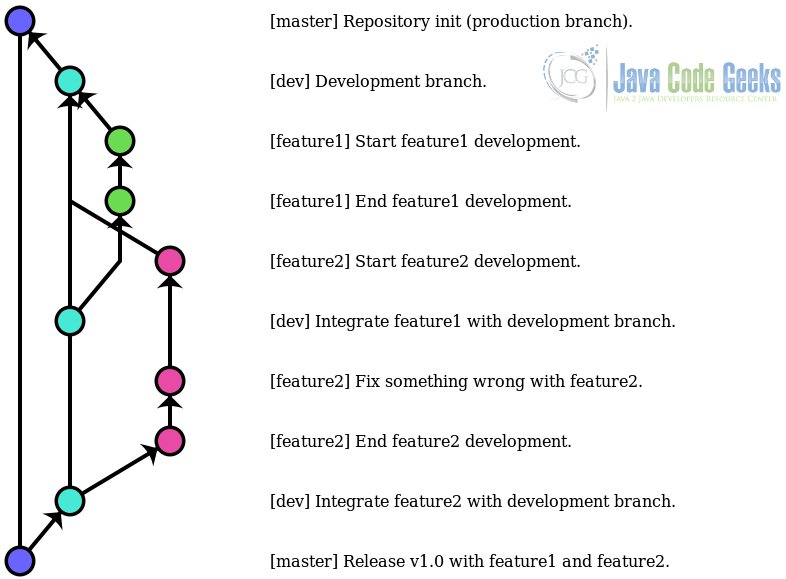

The following graph shows an example of the history of a repository following this strategy:

Simple and clarifying. The production state is only modified for those changes that have been integrated with the development branch, where nothing happens if something breaks. The changes that have to be made for each feature are perfectly isolated, favoring the division of tasks among the teammates.

5.2. One version, one branch

This workflow is thought for creating software that will be available and maintained for several versions. In other words, a release does not “overwrite” every previous releases, it would “overwrite” only the release of the branch the release has been made for.

To achieve this, each maintained version has to have its main version, but with a common development path for all of them.

This is done having a branch for every version (usually named PROJECT_NAME_XX_STABLE or similar) for the stable release, the “master” of each version; and having a main branch (and its sub-branches) where the development is made, for which default master branch can be used. When each feature is developed and tested, the master branch can be merged to every wanted stable version.

This branching strategy is based on the long-running, but, in this case, having many “masters” instead of a single one.

Take into account that each feature should have to be tested with each version of the project we want to apply this feature to. Consider using Continuous Integration when dealing with this strategy.

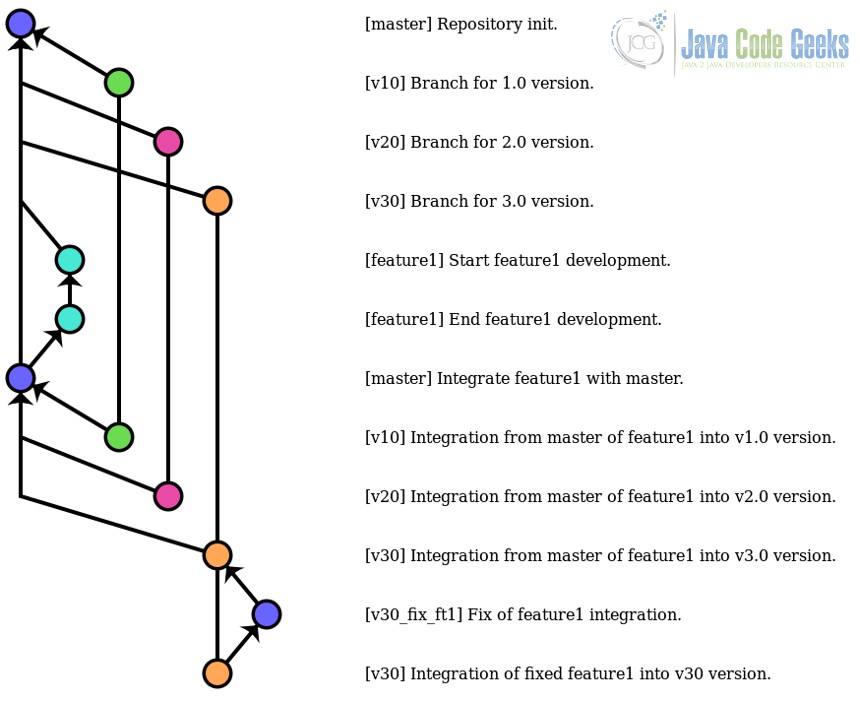

Let’s see an example of the graph of a history for which this strategy has been applied.

As we can see, here, the master branch is used as the main development branch.

In the v3.0 version, we have simulated a bug for feature1. It does not have to be necessarily a bug appeared at integration time, it can be a bug that has been detected later. In any case, we are sure that bug of feature1 only exists for v3.0 version. In these cases, we shouldn’t fix these bugs in master branch, because it’s not something that affects all the versions. We should create a branch from the affected version, fix the bug, and merge to the specific branch. And, if the future the same error persists for new releases, we can consider the option of merging it to master.

The main advantage of this strategy is that the common features follow a common path, and the specific changes can be perfectly isolated for the affected versions.

5.3. Regardless the branching strategy: one branch for each bug

No matter the branching strategy you use, an advisable practice is to create an independent branch for every bug, as same as it has been reported in your bug tracker (because you use a bug tracking system, right?). Actually, we have seen this practice in the previous example, in the integration of the feature into the branch for v3.0 version. Having an independent branch for each bug allows to having the issues perfectly located and identified, having the changes fixed involves isolated from others.

Identifying this branch with the id number generated by the bug tracker for the given bug, naming the branches, for example, as issue-X, allows to have a track between the changes made for the fix of that bug, to the comments made in the corresponding ticket of the bug tracker, which is really helpful, since you can explain possible solutions for the bugs, attach images, etc.

6. Remote repositories

Git, as we have seen in the introduction, is a distributed VCS. This means that, apart from the local, we can have a copy of the repository hosted in a remote server that, apart from making public the source code of the project, is used for collaborative development.

The most popular platform for Git repositories hosting is GitHub. Unfortunately, GitHub does not offer private repositories in its free plan. If you need a hosting platform with unlimited private repositories, you can use Bitbucket. And, if you are looking for hosting your repositories in your own server, the available option is GitLab.

For this section, we will need to use one of the options mentioned above.

6.1. Writing changes in the remote

The first thing we need to do in the remote hosting is to create a repository, for which a URL with the following format will be created:

https://hosting-service.com/username/repository-name

Once having a remote repository, we have to link it with our local repo. This is made with the remote add <remote-name> <repo-url> command:

git remote add origin https://hosting-service.com/username/repository-name

origin is which is named by default by Git, similarly to master branch, but it does not have to be necessarily.

Now, in our local repository, the remote repository is identified as origin. We can now start to “send” information to it, which is made with push option:

git push [remote-name] [branch-name | --all] [--tags]

Let’s see some examples of how it works:

git push origin --all # Updates the remote with all the local branches git push origin master dev # Updates remote's mater and dev branches git push origin --tags # Sends tags to remotes

This is an example output of a successful master branch update:

Counting objects: 3, done. Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 235 bytes | 0 bytes/s, done. Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0) To https://hosting-service.com/username/repository-name.git * [new branch] master -> master

What has Git internally with this?

Well, now, a directory .git/refs/remotes has been created, and, inside it, another directory, origin (because that’s the name we have given to the remote). Here, Git creates a file for each branch exiting in the remote repository, with a reference to it. This reference is just the SHA1 id of the last commit of the given branch of the remote repository. This is used by Git to know if in remote repo are any changes that can be applied to the local repository. We will cover this in detail later in the following sections.

Note: a repository can have as many remotes as we want. For example, we could have the remote of the same repository in both GitHub and Bitbucket:

git remote add github https://github.com/username/repository-name git remote add bitbucket https://bitbucket.org/username/repository-name

6.2. Cloning a repository

The cloning of a repository is actually made once, when we are going to start to work with a remote repository.

For cloning remote repositories there’s no mystery, we just have to use the clone option, specifying the URL of the repository:

git clone https://hosting-service.com/username/repository-name

Which would create a local directory with the repository, with the reference to the remote it has been cloned from.

By default, when cloning a repository, only the default branch is created (master, generally). The way to create the other branches locally is making a checkout to them.

Remote branches can be shown with branch option with -r flag:

git branch -r

They will be shown with the format <remote-name>/<branch-name>. To create the local branch, is enough to make a checkout to <branch-name>.

6.3. Updating remote references: fetching

Fetching the remote repository means updating the reference of a local branch, to put it even with the remote branch.

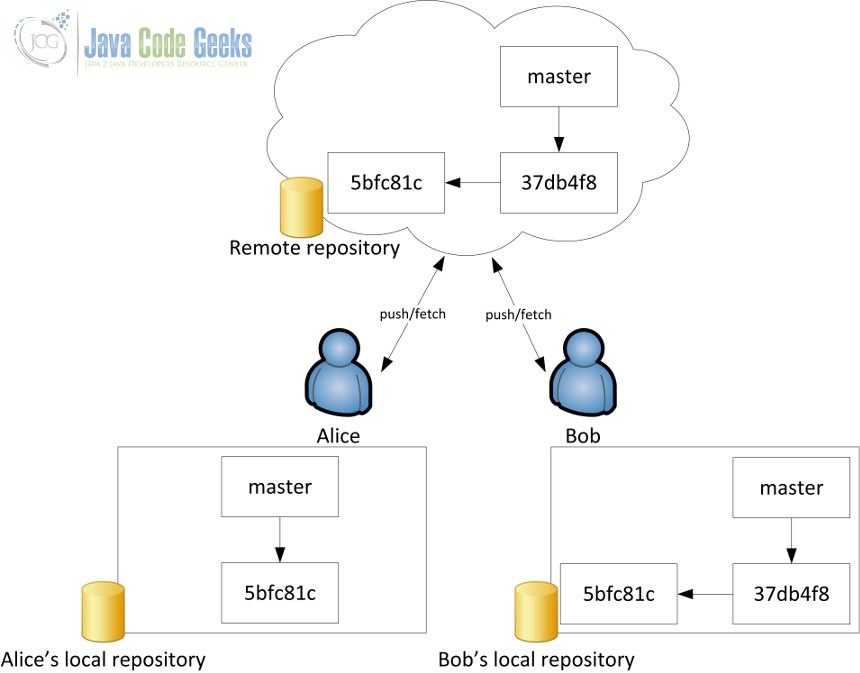

Let’s consider a collaborative scenario where two developers are pushing changes to the same repo. In some moment, one of the developers wants to update its reference to master, to the last push of the other developer, as is shown in the following image.

The content of the .git/refs/remotes/origin/master file of Alice’s repository would be, before any update, the following:

5bfc81ce5f7a0b26b493be0c99f1966a1896c972

Bob’s, however, will be updated, since it has been him the last who has updated the remote repository:

37db4f82e346665f6048cc9e4b7cd48c83c6ebcb

Now, Alice wants to have in her local repository the changes made by Bob. For that, she has to fetch the master branch:

git fetch origin master

(Alternatively, she can fetch every branch with --all flag):

git fetch --all

The output of the fetch would be something similar to the following:

remote: Counting objects: 3, done. remote: Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0) Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done. From https://hosting-service.com/alice/repository-name * branch master -> FETCH_HEAD 5bfc81c..37db4f8 master -> origin/master

And, now, the content of Alice’s .git/refs/remotes/origin/master file would be the same of remote’s:

37db4f82e346665f6048cc9e4b7cd48c83c6ebcb

With this, Alice has updated the reference to remote’s master branch, but the changes have not been applied in the repository.

fetch does not apply changes directly to the local repository. Is the first of two steps that have to be made. The other step is to merge the remote branch, which has just been updated; with the local branch. This is just a merge as any other, but where the remote name has to be indicated:

git merge origin/master

Once the merge is finished, Alice will have the latest version of master branch.

Note: in this merge, we have not applied the no-fast forward. In this cases, would not have many sense to apply it, since we are merging the intrinsically same branch, but that is located somewhere else.

6.4. Fetching and merging remotes at once: pulling

Git has an option to apply remote changes at once, that is, fetching and merging the branch in one command. This option is pull.

Considering the exactly same scenario seen above, we could just execute:

git pull origin master

And would do the fetch, followed by the merge.

Use the way you fell more comfortable with. There’s no better way; actually, they do exactly the same, but expressed differently.

6.5. Conflicts updating remote repository

Let’s return to the scenario shown above. What would happen if, without updating her local repository, Alice would create a commit and push it to the remote repository? Well, she would receive an ugly message from Git:

! [rejected] master -> master (fetch first) error: failed to push some refs to 'https://hosting-service.com/alice/repository-name.git' hint: Updates were rejected because the remote contains work that you do hint: not have locally. This is usually caused by another repository pushing hint: to the same ref. You may want to first integrate the remote changes hint: (e.g., 'git pull ...') before pushing again. hint: See the 'Note about fast-forwards' in 'git push --help' for details.

The push would be rejected because Alice has not continued the history of the repository from a point that has been already registered in the remote. So, before writing changes in the remote repository, she would need first to fetch & merge, or pull, the remote with her changes.

6.5.1. A bad way to resolve conflicts

There’s still another way, which can not be exactly considered as resolving. Is about forcing pushes with --force flag.

Forcing a push is about, basically, one thing: overwrite the remote repository branch (or the whole repository) with the one that is being pushed. So, in the above scenario, if Alice forces a push of her repository, the 37db4f8 commit will disappear. This would leave Bob working in something similar to a “parallel universe” that cannot coexist with the current reality of the project, since his work is based on a state that no longer exist in the project.

In conclusion, don’t force pushes when you are working with other developers, at least if you don’t want to have an intense argument with them.

If you Google for “git force push” in the images section, you will see some memes that perfectly explain graphically what a forced push is considered as.

6.6. Deleting things in remote repository

As with forced pushes, things in remote repositories must be deleted with extreme precaution. Before deleting anything, every collaborator should be informed about it.

Actually, when we are pushing commits, branches, etc., we are pushing them to a ref destination, but we don’t have to specify the destination explicitly.

The explicit syntax is the following:

git push origin <source>:<destination>

So, the way of deleting remote things is updating the refs to prior states, or pushing “nothing”.

Let’s see how to do it for every case.

6.6.1. Deleting commits

This is just the same as deleting commits locally, for example, to delete the last two commits:

git push origin HEAD~2:master --force

If we are using HEAD to refer the commits to remove, we must ensure that it’s located on the same branch as remote.

Note that these pushes have to be forced too.

6.6.2. Deleting branches

This is quite simple, is just about pushing “nothing”, as said before. The following would remove dev branch from remote repository:

git push origin :dev

Remote branches should be removed when the local branch is removed.

6.6.3. Deleting tags

As same as with branches, we have to push “nothing”, e.g.:

git push origin --tags :v1.0

7. Patches

You will have probably ever seen a software being updated with something called patch. A patch is just a file that describes the changes that have to be made over a program, indicating which code lines have to be removed, and which have to be added. With Git, a path is just the output of a diff saved into a file.

Take into account that a patch is an update, but an update does not have to be a patch necessarily. Patches are thought for hotfixes, or also critical features that have to be fixed or implemented right now, not for being the common update and deploying strategy.

7.1. Creating patches

As said, a patch for Git is just the output of a diff. So, we would have to redirect that output to a file:

git diff <expression> > <patch-name>.patch # The extension is not important.

For example:

git diff master..issue-1 > issue-1-fix.patch

Note: a patch cannot be modified. If a patch file suffers any modification, Git will mark it as corrupt and it won’t apply it.

7.2. Applying patches

The patches are applied with apply command. It’s as simple as specifying the path to the path file:

git apply <patch-file>

If patching goes well, no message will be displayed (if you haven’t used the --verbose flag). If the patch is not applicable, Git will show which are the files causing problems.

Is quite common to get errors due to just whitespace differences. These errors can be ignored with --ignore-space-change and --ignore-whitespace flags.

8. Cherry picking

There may be some scenarios in where we are interested in porting into a branch just a specific set of changes made on another branch, instead of merging it.

To do this, Git allows to cherry pick commits from branches, with the cherry-pick command. The mechanism is the same as merging, but, in this case, specifying the commit SHA1 id, for example:

git cherry-pick -x aba6c1b # Several commits can be cherry picked.

A cherry pick creates a new commit, with the same message as the original’s one. The -x option is for adding to that commit message a line indicating that is a cherry pick, and from which commit has been picked:

(cherry picked from commit aba6c1bf9a0a7d6d9ccceeab2b5dfc64f6c115c2)

The cherry picking should not be a recurrent practice in your workflow, since it does not leave a track in the history, just a line indicating where has been picked from.

9. Hooks

Git hooks are custom scripts that are triggered when important events occur, for example, a commit or a merge.

Let’s say that you want to notify someone with an email when your production branch is updated, or to run a test suite; but in an automated way. The hooks can do this for you.

The scripts are located in .git/hooks directory. By default, some sample hooks are provided. Each hook has to have a concrete name, that we will see later, with no extension; and has to be marked as executable. You can use other scripting languages such us PHP or Python, apart from shell code.

There are two kind of hooks: client-side, and server-side.

9.1. Client-side hooks

The client-side hooks are those that are fired when the local repository suffers changes. These are the most common:

pre-commit: invoked bygit commitcommand, before the commit is saved. A commit can be aborted with this hook exiting with a non-zero status.post-commit: invoked bygit committoo, but this time when the commit has been saved. At this point, the commit cannot be aborted.post-merge: as same as withpost-commit, but being this one fired bygit merge.pre-push: fired bygit push, before the remote any object has been transferred.

The following script shows an example applicable for both post-commit and post-commit hooks, for notification purposes:

#!/bin/sh branch=$(git rev-parse --abbrev-ref HEAD) if [ "$branch" = "master" ]; then echo "Notifying release to everyone..." # Send the notification... fi

To use it for both cases, you would have to create both hooks.

9.2. Server-side hooks

These hooks reside in the server where the remote repository is hosted. As it is obvious, if you are using services such as GitHub for hosting your repositories, you won’t be permitted to execute arbitrary code. In GitHub’s case, you have available third-party services, but never hooks with your own code. For using executing your code, you will have to have your own server for hosting.

The most used hooks are:

pre-receive: this is fired after someone makes a push, and before the references get updated in the remote. So, with this hook, you can deny any push.update: almost exact to the previous one, but this is executed for each reference pushed. That is, if 5 references have been pushed, this hook will be executed 5 times, unlikepre-receive, which is executed for the push as a whole.post-receive: this one is executed once the push has been successful, so it can be used for notification purposes also.

9.3. Hooks are not included in the history

The hooks only exist in the local repository. If you make a push in a repository that has custom hooks, these will not be sent to the remote. So, if every developer should share the same hooks, they would have to be included in the working directory, and installed them manually.

10. An approach to Continuous Integration

Continuous Integration (CI) is a software engineering practice that is closely related to version controlling, and it’s worth mentioning it, at least to know it conceptually.

CI consists on making several integrations of the code (at least, once a day), in a completely automated way, with the aim of finding errors in early phases of the development.

The concept is almost the same of the hooks, but in a much more scalable and maintainable way.

Here are some of the actions that are performed in each integration:

- Test execution: unit, acceptance, integration, regression, and a large etc.

- Quality Assurance, with software metrics checking: cyclomatic complexity, code coverage, and another large etc.

- Software coding standard compliance checking.

Continuous Integration allows to perform those actions, and more, automatically, without the need of having to execute it manually, just with a push or commit. Interesting, isn’t it?

Probably, the most used CI options are the following:

- Travis CI: cloud-based, which allows to fire integrations with pushes, without the need of having your own server.

- Jenkins: self-hosted, for which a server is needed, but which is completely configurable. Compatible with many build tools, like Ant, Gradle, Maven, Phing, Grunt…

11. Conclusion

Version control systems help to fulfill one of the dreams of every developer: having identified each point of the entire history of a project, being able to return to any point at any time. The VCS we have seen in this guide is Git, the preferred by the software developer community.

After reading this guide, if it’s your first time with Git, you will probably be thinking how couldn’t you live without Git until today.

12. Resources

The best resource possible is Pro Git (2nd edition), by Scott Chacon and Ben Straub, which covers almost every topic about Git. You can read it free at Git official page.

Thanks, Julen, for the detailed, well explained, GIT / Github tutorial!

Thank you, Gil, for taking your time to read it! ;)

Is this article different from this eBook here: https://webuilddesign.com/git-tutorial-the-ultimate-guide/

how to download books?

Hello,

You can find the pdf version of this here: https://www.javacodegeeks.com/minibook/git-tutorial but first you have to login. If you don’t have an account you should first create one.