Functional Data Structures in Java 8 with Javaslang

Java 8’s lambdas (λ) empower us to create wonderful API’s. They incredibly increase the expressiveness of the language.

Javaslang leveraged lambdas to create various new features based on functional patterns. One of them is a functional collection library that is intended to be a replacement for Java’s standard collections.

Functional Programming

Before we deep-dive into the details about the data structures I want to talk about some basics. This will make it clear why I created Javaslang and specifically new Java collections.

Side-Effects

Java applications are typically plentiful of side-effects. They mutate some sort of state, maybe the outer world. Common side effects are changing objects or variables in place, printing to the console, writing to a log file or to a database. Side-effects are considered harmful if they affect the semantics of our program in an undesirable way.

For example, if a function throws an exception and this exception is interpreted, it is considered as side-effect that affects our program. Furthermore exceptions are like non-local goto-statements. They break the normal control-flow. However, real-world applications do perform side-effects.

int divide(int dividend, int divisor) {

// throws if divisor is zero

return dividend / divisor;

}In a functional setting we are in the favorable situation to encapsulate the side-effect in a Try:

// = Success(result) or Failure(exception)

Try<Integer> divide(Integer dividend, Integer divisor) {

return Try.of(() -> dividend / divisor);

}This version of divide does not throw any more. We made the possible failure explicit by using the type Try.

Referential Transparency

A function, or more general an expression, is called referential transparent if a call can be replaced by its value without affecting the behavior of the program. Simply spoken, given the same input the output is always the same.

// not referential transparent Math.random(); // referential transparent Math.max(1, 2);

A function is called pure if all expressions involved are referential transparent. An application composed of pure functions will most probably just work if it compiles. We are able to reason about it. Unit tests are easy to write and debugging becomes a relict of the past.

Thinking in Values

Rich Hickey, the creator of Clojure, gave a great talk about The Value of Values. The most interesting values are immutable values. The main reason is that immutable values

- are inherently thread-safe and hence do not need to be synchronized

- are stable regarding equals and hashCode and thus are reliable hash keys

- do not need to be cloned

- behave type-safe when used in unchecked covariant casts (Java-specific)

The key to a better Java is to use immutable values paired with referential transparent functions.

Javaslang provides the necessary controls and collections to accomplish this goal in every-day Java programming.

Data Structures in a Nutshell

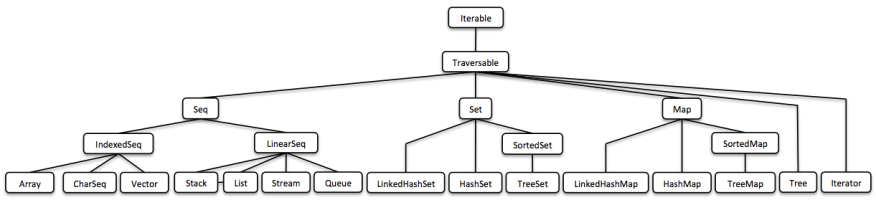

Javaslang’s collection library comprises of a rich set of functional data structures built on top of lambdas. The only interface they share with Java’s original collections is Iterable. The main reason is that the mutator methods of Java’s collection interfaces do not return an object of the underlying collection type.

We will see why this is so essential by taking a look at the different types of data structures.

Mutable Data Structures

Java is an object-oriented programming language. We encapsulate state in objects to achieve data hiding and provide mutator methods to control the state. The Java collections framework (JCF) is built upon this idea.

interface Collection<E> {

// removes all elements from this collection

void clear();

}Today I comprehend a void return type as a smell. It is evidence that side-effects take place, state is mutated. Shared mutable state is an important source of failure, not only in a concurrent setting.

Immutable Data Structures

Immutable data structures cannot be modified after their creation. In the context of Java they are widely used in the form of collection wrappers.

List<String> list = Collections.unmodifiableList(otherList);

// Boom!

list.add("why not?");There are various libraries that provide us with similar utility methods. The result is always an unmodifiable view of the specific collection. Typically it will throw at runtime when we call a mutator method.

Persistent Data Structures

A persistent data structure does preserve the previous version of itself when being modified and is therefore effectively immutable. Fully persistent data structures allow both updates and queries on any version.

Many operations perform only small changes. Just copying the previous version wouldn’t be efficient. To save time and memory, it is crucial to identify similarities between two versions and share as much data as possible.

This model does not impose any implementation details. Here come functional data structures into play.

Functional Data Structures

Also known as purely functional data structures, these are immutable and persistent. The methods of functional data structures are referential transparent.

Javaslang features a wide range of the most-commonly used functional data structures. The following examples are explained in-depth.

Linked List

One of the most popular and also simplest functional data structures is the (singly) linked List. It has a head element and a tail List. A linked List behaves like a Stack which follows the last in, first out (LIFO) method.

In Javaslang we instantiate a List like this:

// = List(1, 2, 3) List<Integer> list1 = List.of(1, 2, 3);

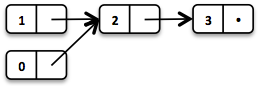

Each of the List elements forms a separate List node. The tail of the last element is Nil, the empty List.

This enables us to share elements across different versions of the List.

// = List(0, 2, 3) List<Integer> list2 = list1.tail().prepend(0);

The new head element 0 is linked to the tail of the original List. The original List remains unmodified.

These operations take place in constant time, in other words they are independent of the List size. Most of the other operations take linear time. In Javaslang this is expressed by the interface LinearSeq, which we may already know from Scala.

If we need data structures that are queryable in constant time, Javaslang offers Array and Vector. Both have random access capabilities.

The Array type is backed by a Java array of objects. Insert and remove operations take linear time. Vector is in-between Array and List. It performs well in both areas, random access and modification.

In fact the linked List can also be used to implement a Queue data structure.

Queue

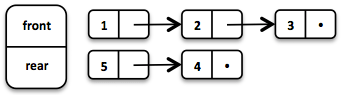

A very efficient functional Queue can be implemented based on two linked Lists. The front List holds the elements that are dequeued, the rear List holds the elements that are enqueued. Both operations enqueue and dequeue perform in O(1).

Queue<Integer> queue = Queue.of(1, 2, 3)

.enqueue(4)

.enqueue(5);The initial Queue is created of three elements. Two elements are enqueued on the rear List.

If the front List runs out of elements when dequeueing, the rear List is reversed and becomes the new front List.

When dequeueing an element we get a pair of the first element and the remaining Queue. It is necessary to return the new version of the Queue because functional data structures are immutable and persistent. The original Queue is not affected.

Queue<Integer> queue = Queue.of(1, 2, 3);

// = (1, Queue(2, 3))

Tuple2<Integer, Queue<Integer>> dequeued =

queue.dequeue();What happens when the Queue is empty? Then dequeue() will throw a NoSuchElementException. To do it the functional way we would rather expect an optional result.

// = Some((1, Queue())) Queue.of(1).dequeueOption(); // = None Queue.empty().dequeueOption();

An optional result may be further processed, regardless if it is empty or not.

// = Queue(1)

Queue<Integer> queue = Queue.of(1);

// = Some((1, Queue()))

Option<Tuple2<Integer, Queue<Integer>>>

dequeued = queue.dequeueOption();

// = Some(1)

Option<Integer> element =

dequeued.map(Tuple2::_1);

// = Some(Queue())

Option<Queue<Integer>> remaining =

dequeued.map(Tuple2::_2);Sorted Set

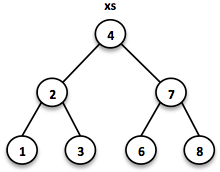

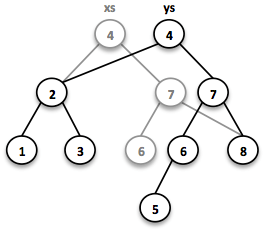

Sorted Sets are data structures that are more frequently used than Queues. We use binary search trees to model them in a functional way. These trees consist of nodes with up to two children and values at each node.

We build binary search trees in the presence of an ordering, represented by an element Comparator. All values of the left subtree of any given node are strictly less than the value of the given node. All values of the right subtree are strictly greater.

// = TreeSet(1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8)

SortedSet<Integer> xs =

TreeSet.of(6, 1, 3, 2, 4, 7, 8);Searches on such trees run in O(log n) time. We start the search at the root and decide if we found the element. Because of the total ordering of the values we know where to search next, in the left or in the right branch of the current tree.

// = TreeSet(1, 2, 3);

SortedSet<Integer> set = TreeSet.of(2, 3, 1, 2);

// = TreeSet(3, 2, 1);

Comparator<Integer> c = (a, b) -> b - a;

SortedSet<Integer> reversed =

TreeSet.of(c, 2, 3, 1, 2);Most tree operations are inherently recursive. The insert function behaves similar to the search function. When the end of a search path is reached, a new node is created and the whole path is reconstructed up to the root. Existing child nodes are referenced whenever possible. Hence the insert operation takes O(log n) time and space.

// = TreeSet(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8) SortedSet<Integer> ys = xs.add(5);

In order to maintain the performance characteristics of a binary search tree it needs to be kept balanced. All paths from the root to a leaf need to have roughly the same length.

In Javaslang we implemented a binary search tree based on a Red/Black Tree. It uses a specific coloring strategy to keep the tree balanced on inserts and deletes. To read more about this topic please refer to the book Purely Functional Data Structures by Chris Okasaki.

State of the Collections

Generally we are observing a convergence of programming languages. Good features make it, other disappear. But Java is different, it is bound forever to be backward compatible. That is a strength but also slows down evolution.

Lambda brought Java and Scala closer together, yet they are still so different. Martin Odersky, the creator of Scala, recently mentioned in his BDSBTB 2015 keynote the state of the Java 8 collections.

He described Java’s Stream as a fancy form of an Iterator. The Java 8 Stream API is an example of a lifted collection. What it does is to define a computation and link it to a specific collection in another excplicit step.

// i + 1 i.prepareForAddition() .add(1) .mapBackToInteger(Mappers.toInteger())

This is how the new Java 8 Stream API works. It is a computational layer above the well known Java collections.

// = ["1", "2", "3"] in Java 8

Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3)

.stream()

.map(Object::toString)

.collect(Collectors.toList())Javaslang is greatly inspired by Scala. This is how the above example should have been in Java 8.

// = Stream("1", "2", "3") in Javaslang

Stream.of(1, 2, 3).map(Object::toString)Within the last year we put much effort into implementing the Javaslang collection library. It comprises the most widely used collection types.

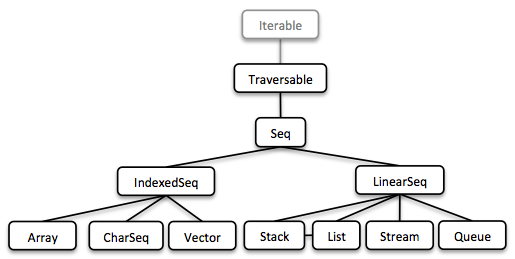

Seq

We started our journey by implementing sequential types. We already described the linked List above. Stream, a lazy linked List, followed. It allows us to process possibly infinite long sequences of elements.

All collections are Iterable and hence could be used in enhanced for-statements.

for (String s : List.of("Java", "Advent")) {

// side effects and mutation

}We could accomplish the same by internalizing the loop and injecting the behavior using a lambda.

List.of("Java", "Advent").forEach(s -> {

// side effects and mutation

});Anyway, as we previously saw we prefer expressions that return a value over statements that return nothing. By looking at a simple example, soon we will recognize that statements add noise and divide what belongs together.

String join(String... words) {

StringBuilder builder = new StringBuilder();

for(String s : words) {

if (builder.length() > 0) {

builder.append(", ");

}

builder.append(s);

}

return builder.toString();

}The Javaslang collections provide us with many functions to operate on the underlying elements. This allows us to express things in a very concise way.

String join(String... words) {

return List.of(words)

.intersperse(", ")

.fold("", String::concat);

}Most goals can be accomplished in various ways using Javaslang. Here we reduced the whole method body to fluent function calls on a List instance. We could even remove the whole method and directly use our List to obtain the computation result.

List.of(words).mkString(", ");In a real world application we are now able to drastically reduce the number of lines of code and hence lower the risk of bugs.

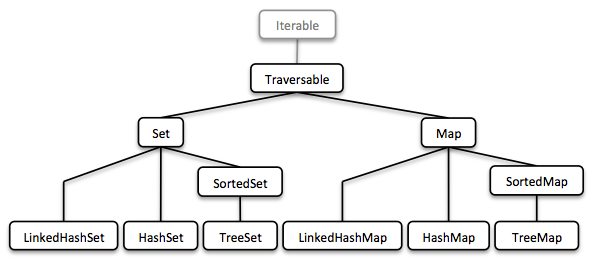

Set and Map

Sequences are great. But to be complete, a collection library also needs different types of Sets and Maps.

We described how to model sorted Sets with binary tree structures. A sorted Map is nothing else than a sorted Set containing key-value pairs and having an ordering for the keys.

The HashMap implementation is backed by a Hash Array Mapped Trie (HAMT). Accordingly the HashSet is backed by a HAMT containing key-key pairs.

Our Map does not have a special Entry type to represent key-value pairs. Instead we use Tuple2 which is already part of Javaslang. The fields of a Tuple are enumerated.

// = (1, "A") Tuple2<Integer, String> entry = Tuple.of(1, "A"); Integer key = entry._1; String value = entry._2;

Maps and Tuples are used throughout Javaslang. Tuples are inevitable to handle multi-valued return types in a general way.

// = HashMap((0, List(2, 4)), (1, List(1, 3)))

List.of(1, 2, 3, 4).groupBy(i -> i % 2);

// = List((a, 0), (b, 1), (c, 2))

List.of('a', 'b', 'c').zipWithIndex();At Javaslang, we explore and test our library by implementing the 99 Euler Problems. It is a great proof of concept. Please don’t hesitate to send pull requests.

Hands On!

I really hope this article has sparked your interest in Javaslang. Even if you do use Java 7 (or below) at work, as I do, it is possible to follow the idea of functional programming. It will be of great good!

Please make sure Javaslang is part of your toolbelt in 2016.

Happy hacking!

PS: question ? @_Javaslang or Gitter chat

| Reference: | Functional Data Structures in Java 8 with Javaslang from our JCG partner Daniel Dietrich at the Java Advent Calendar blog. |