Features do not a Product Roadmap Make

Last month, Mike Smart of Egress Solutions and I gave a webinar for Pragmatic Marketing on product roadmapping when working in agile environments. We had a great turnout of over 1500 people in the session – with not nearly enough time to answer all of the questions.

One attendee asked, “Please explain how a prioritized list of features is not a roadmap?”

A fantastic question, which we did not see in time to answer during the call.

Why and What and When

The shortest answer I can come up with for the question – and probably all we would have had time to address during the call is the following:

A roadmap tells you both “why” and “what;” a list of features tells you only “what.” #prodmgmt

If all you need is the answer above, then this is a really short article for you – you can stop here. There is some nuance to the above statement, which helps you address something more valuable – having a good roadmap. If that’s interesting, then keep reading.

Which What?

Seven years ago this month, I joined in the fracas stirred up by an article where the author

- Described something (bad) which was not a roadmap

- Called it a roadmap, then

- Concluded that roadmaps are bad.

I would describe the author’s complaints [about roadmaps] as a list of things which can go wrong when you treat a list of features as if it were a roadmap.

Seven years later, this is still a source of confusion. Perhaps it is the logical conclusion of anointing people with the title of “product manager” and not giving them the training, tools, and mentorship needed to learn the craft while simultaneously doing the work.

Some of the confusion may come from how we talk about roadmaps. My tweetably short answer above leaves something to be desired.

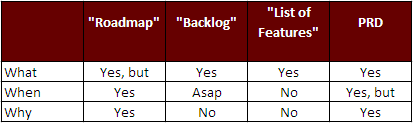

All of the different containers for requirements document “what” the team will be building. The different containers do this in different ways – and the roadmap has a qualifier.

- PRD – identifies all the things which the team will build*, and the context in which those items are relevant or organized (e.g. the “Shopping Cart” section of the PRD for an ecommerce website will include the requirements for including controls that allow a user to update the quantity of items in the cart).

- List of Features – possibly the most abhorrent of the containers – in the midst of a long list, will be the requirement to include an “update quantity” control with every item in the shopping cart. If you’re lucky, the requirement will be tagged with “shopping cart” for ease of organizing / tracking progress. Given the lack of context provided by a list of features, this requirement might be preceded by the “update inventory levels” requirement and followed by the “update user profile picture” requirement.

- Backlog – when someone takes a list of features and sorts them by “give me this first” you get a backlog. The story at the top of the list may be “As a [shopper in a hurry, who is multitasking while waiting in line at the DMV] I need to be able to update the quantity of items in my shopping cart because someone jostled me and I double-tapped my phone when I meant to single-tap, so that I only purchase the quantity I intended.” The question too many people are happy to dodge is why is this story at the top of the list? We’ll have to come back to that another time.

- Roadmap – “Yes, but” is consultant speak for “I’m answering your question, but let me tell you the question you should have asked – and the answer to that question as well.” If your roadmap says “Will include update quantity control in shopping cart” you’re doing it wrong. Your roadmap should say “Improved shopping experience on mobile” or “Better shopping experience for spearfisher persona.” Those descriptions of “what” are at a higher level, and articulate intentionality. So, yes, a roadmap includes “what” – but not the same “what” as a backlog.

*As an aside – the team won’t actually build all of the stuff in the PRD, nor will they build what they build when the PRD says it will happen, and it will be over-budget. But that’s another discussion entirely – and a big part of why “agile” came into existence in the first place.

When a roadmap is being used to communicate “what” the product will be, it should be in the language of describing which problems will be addressed, for whom, or in what context. This is the most important type of theme which would be part of a thematic roadmap. Other themes could be “improve our positioning relative to competitor X” or “fill in a missing component in our portfolio strategy.”

Context in Design

Requirements, by their nature, live in a particular context. At one elevation or perspective, something is a requirement, defining and constraining what must be done; in a different context, that same something is a design choice representing a choice about how to do what must be done.

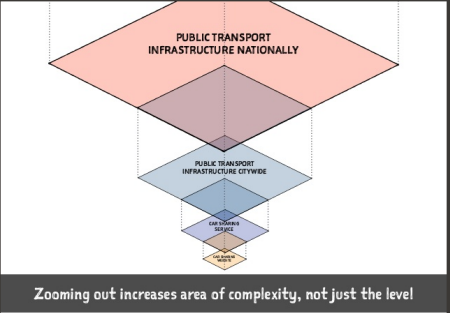

Several months ago, Andy Polaine posted a presentation about the future of UX, in which he presented a compelling imagery establishing the context in which design decisions are made.

To fully appreciate the power of what Andy is talking about, I believe you have to view the above slide (#55), in the context of his presentation. After experiencing it that way, the imagery has infused itself into how I frame product management activities.

If you cannot make time for now, the metaphor still works – solving the “visible and available” problem happens in the context of a wider environment (a larger, more complex problem), which is itself in the context of a wider environment, etc.

I find that I also apply the same concept when thinking about investments across differing time horizons.

On a given day, a member of the product team is implementing the code for adjusting the quantity of an item in the shopping cart. Implementation is not the rote mechanical movements of a machine – it is a series of choices and actions.

Those implementation decisions happen within the context of implementing a story from the top of the backlog – helping someone place orders on their phone while waiting in line somewhere. This context informs choices (like not requiring a modal dialogue to confirm the user’s choice when making a change in quantity, or making the change to “quantity of zero” be an explicit and distinct interaction).

The decision to prioritize empowering mobile users this quarter comes within the context of a decision to focus on 18 to 26 year olds as a key demographic for our product sales. Improvements to the mobile shopping experience happen in conjunction with a change in inventory, a partnership with another company, and a targeted advertising campaign.

The focus on this particular group of customers is a “business design” choice as well.

Context in Agile

A backlog lives within a roadmap, it does not replace it #agile #prodmgmt

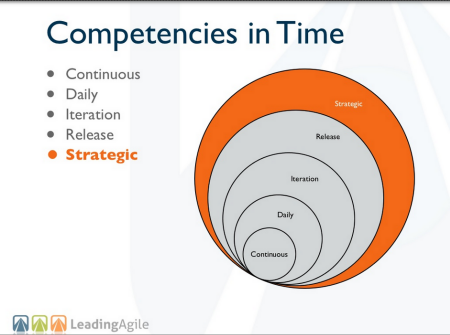

A similar perspective on context is presented by Mike Cottmeyer of Leading Agile when looking at how you put the work the teams are doing into context. A “release backlog” or “product backlog” is defined within the context of strategy – which is manifested in the roadmap.

Mike’s slide (#92 in a great deck) stops with “strategic” context for a release. He and I have talked about this, and I believe we have strikingly similar views on context. This view marries both the time-horizon and the problem-definition notions of context, from the perspective of the person doing the work and understanding the “why” of doing the work.

Within each context is framed a set of choices – providing both boundaries and flexibility to adapt to what we learn, but at a lower level of detail, with less ultimate potential value, for a shorter period of time.

Conclusion

A backlog – a prioritized list of features – is not a roadmap. It is a reflection of a set of design choices which happen to fulfill in product what the roadmap sets out as a manifestation of strategy.

A roadmap tells you both “why” and “what;” a backlog tells you only “what.” #agile #prodmgmt

| Reference: | Features do not a Product Roadmap Make from our JCG partner Scott Sehlhorst at the Tyner Blain’s blog blog. |