Faster Java Startup with Checkpoint Restore at Main

The Java Virtual Machine provides a managed

runtime environment for applications that have been compiled into bytecodes (but may not have necessarily

been written in Java). This offers

numerous benefits to application developers and, often, improved performance

over code statically compiled for a specific platform. The JVM handles memory allocation and

recovery automatically via the garbage

collector (GC), reducing the potential for memory leaks. Just-in-time

(JIT) compilation provides the “write once, run anywhere” ability,

eliminating the need to build separate binary versions of an application for

each platform supported.

These advantages are not entirely without

cost, though. Although the overall speed

of an application running on the JVM may be ultimately faster, there is a warm-up time required, as frequently

used methods are compiled and optimized.

Each time an application is started the same profiling, analysis and

compilation must be performed, even if the application is being used identically.

Azul Systems has, for many years, been working on ways to minimize the performance impact of these aspects of the JVM. The Zing JVM uses the Falcon JIT compiler in place of the old C2 JIT and ReadyNow! technology to record a profile that can be used when restarting an application.

Azul’s Zulu build of OpenJDK now includes a similar set of technologies, which we call Checkpoint/Restore at Main (CRaM).

The idea of CRaM is to reduce the warm-up

time of an application by performing a training

run, which can then be used during a production

run. Training runs can be performed

in three different ways:

- The application is used, as

normal, and performs whatever functions are necessary. The application terminates by exiting the

main() method. At this point, all data

from the application run is recorded. No

changes are required to application code; adding the -Zcheckpoint JVM flag is

all that is required. - The application is used, as per

scenario 1, above, but terminates by calling System.exit(). Again, no changes are required to the

application code, but, in this case, the JVM flag,

-Dcom.azul.System.exit.doCheckpointRestore=true must be used. - In this scenario, the developer

chooses a specific point in the application code where they would like to

generate a checkpoint. Changes to the

application code are necessary; a call to the method, Dcom.azul.System.tryCheckpointRestore(),

is placed where required. This is useful

for applications that do not terminate.

The call is ignored unless the -Zcheckpoint flag is specified for the

JVM. An additional flag,

-XX:CRTrainingCount, is available to enable an application to process more than

one transaction before recording the checkpoint.

The checkpoint is a sophisticated snapshot

of the state of the application when it is created. It includes the following information:

- The JVMs internal

representation of Java classes. Each

time an application starts, it needs to read the required classes and create

its own representation of each class with initialized data. - The code that has been

generated by the JVM JIT compilers, C1 and C2.

Because of the way this code is reused, it is necessary to turn off

certain optimizations to enable the code to be reused in a production run. - Initialized system

classes. These are classes from the core

class libraries and is independent of any application code. - Certain Java objects from the

heap that are related to the startup of the application.

There are strict limitations to where a

checkpoint can be used for a production run.

A checkpoint is closely tied to the platform used for the training run,

and it includes very low-level information, such as memory pages from mapped

system libraries like libc. A checkpoint

will not work if changes are made to system libraries, the JDK or the

application code before a production run is performed. Checkpoints should only be shared between

machines running the same hardware and software stack.

To use a checkpoint for a production run,

you would use a command-line like this:

java -Zrestore myAppClass <application arguments>

The previously stored checkpoint data will

be used to minimize, as far as possible, the warm-up time associated with the

application. There are a couple of

important points to note:

- During the production run, code

may be recompiled as a normal part of the JIT compilation process. Unlike during the training run, all optimizations

available to the JIT will be enabled. - The application needs to be

started from the same directory where the training run was generated. This is part of the state of the checkpoint. - No JVM command-line flags

should be used. A training run is tied

to the command line flags used during its creation, and these are then automatically

set during a production run. Changing

them could invalidate the information in the checkpoint.

Currently, the CRaM functionality is

targeted at embedded applications, where the ability to run at optimum speed

from startup is vital. As such, the

supported platforms for CRaM are Arm 32-bit processors only, running Linux with

a kernel of 3.5, or higher and glibc version 2.13, or higher. CRaM includes a utility, cr-compat-checker,

that can be used to verify that a device meets these requirements.

To determine whether CRaM is appropriate

for an application, it is crucial to understand how it changes the performance

profile of the application. CRaM is

designed to reduce the time taken to get to the point where the checkpoint was

generated. Execution from that point on

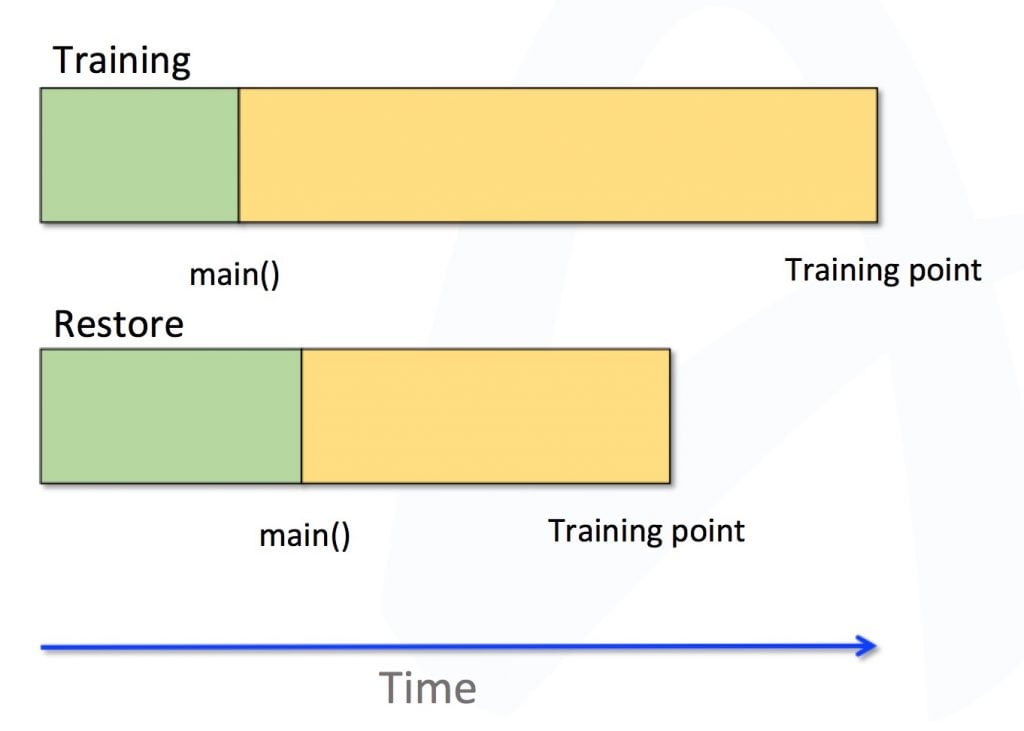

will be unchanged whether a checkpoint has been used or not. When looking at the performance of a Java

application, it can be divided into two parts: JVM startup time, i.e. time to

get to the main() entry point; and time running from main(). When using CRaM, the time required to get to

main() will be longer, but the time needed to get to where the checkpoint was

created will be less.

To make this easier to understand, a

diagram is useful:

As an example, consider a simple Spring

Boot application.

Without using CRaM, the time to main() was

2 seconds and the time from entering main() to a fully initialized application,

ready to process transactions was 31 seconds. The time required, therefore, before a

transaction could be processed was 33 seconds.

Having taken a checkpoint, using CRaM to

start the application, time to main() was increased to 3 seconds. However, the time from entering main() to

fully initialized was only 18 seconds.

This reduces the time required before a transaction can be processed to

only 21 seconds, which is substantially quicker.

As you can see, CRaM can make a significant

difference in the effectiveness of applications that need to be ready to

perform tasks as quickly as possible.

This is especially important in embedded applications, where resources

are constrained, and devices may need to be restarted more frequently than a

conventional server.

Azul is currently running beta trials of CRaM. If you are interested in being part of this, please contact us for more information.

CONTACT AZUL FOR MORE INFORMATION