Implied Readability

The hands-on guide to Jigsaw brushes past a feature I would like to discuss in more detail: implied readability. With it, a module can reexport another module’s API to its own dependents.

Overview

This post is based on a section of an article I’ve recently written for InfoQ. If you are interested in a Jigsaw walkthrough, you should read the entire piece.

All non-attributed quotes are from the excellent State Of The Module System.

Definition Of (Implied) Readability

A module’s dependency on another module can take two forms.

Recap: Readability

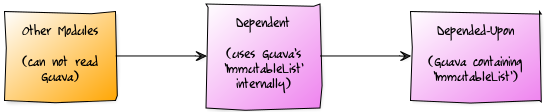

First, there are dependencies that are consumed internally without the outside world having any knowledge of them. In that case, the dependent module depends upon another but this relationship is invisible to other modules.

Take, for example, Guava, where the code depending on a module does not care at all whether it internally uses immutable lists or not.

This is the most common case and it is covered by the concept of readability:

When one module depends directly upon another […] then code in the first module will be able to refer to types in the second module. We therefore say that the first module reads the second or, equivalently, that the second module is readable by the first.

Here, a module can only access another module’s API if it declares its dependency on it. So if a module depends on Guava, other modules are left in the dark about that and would not have access to Guava without declaring their own explicit dependencies on it.

Implied Readability

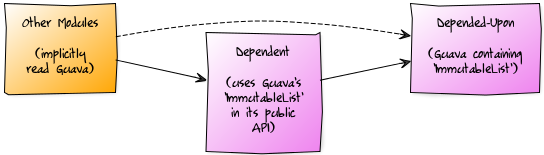

But there is another use case where the dependency is not entirely encapsulated, but lives on the boundary between modules. In that scenario one module depends on another, and exposes types from the depended-upon module in its own public API.

In the example of Guava a module’s exposed methods might expect or return immutable lists.

So code that wants to call the dependent module might have to use types from the depended-upon module. But it can’t do that if it does not also read the second module. Hence for the dependent module to be at all usable, client modules would all have to explicitly depend on that second module as well. Identifying and manually resolving such hidden dependencies would be a tedious and error-prone task.

This is where implied readability comes in:

[We] extend module declarations so that one module can grant readability to additional modules, upon which it depends, to any module that depends upon it. Such implied readability is expressed by including the public modifier in a requires clause.

In the example of a module’s public API using immutable lists, the module would publicly require Guava, thus granting readability to Guava to all other modules depending on it. This way, its API is immediately usable.

Examples

From The JDK

Let’s look at the java.sql module. It exposes the interface Driver, which returns a Logger via its public method getParentLogger(). Logger belongs to java.logging. Because of that java.sql publicly requires java.logging, so any module using Java’s SQL features can also access the logging API.

So the module descriptor of java.sql might look as follows:

module java.sql {

requires public java.logging;

requires java.xml;

// exports ...

}From The Jigsaw Advent Calendar

The calendar contains a module advent.calendar, which holds a list of 24 surprises, presenting one on each day. Surprises are part of the advent.surprise module. So far this looks like a open and shut case for a regular requires clause.

But in order to create a calendar we need to pass factories for the different kinds of surprises to the calendar’s static factory method, which is part of the module’s public API. So we used implied readability to ensure that modules using the calendar would not have to explicitly require the surprise module.

module org.codefx.demo.advent.calendar {

requires public org.codefx.demo.advent.surprise;

// exports ...

}Published by Peter Hopper under CC-BY-NC 2.0

Beyond Module Boundaries

The State Of The Module System recommends when to use implied readability:

In general, if one module exports a package containing a type whose signature refers to a package in a second module then the declaration of the first module should include a requires public dependence upon the second. This will ensure that other modules that depend upon the first module will automatically be able to read the second module and, hence, access all the types in that module’s exported packages.

But how far should we take this?

Looking back on the example of java.sql, should a module using it require java.logging as well? Technically such a declaration is not needed and might seem redundant.

To answer this question we have to look at how exactly our fictitious module uses java.logging. It might only need to read it so we are able to call Driver.getParentLogger(), change the logger’s log level and be done with it. In this case our code’s interaction with java.logging happens in the immediate vicinity of its interaction with Driver from java.sql. Above we called this the boundary between two modules.

Alternatively our module might actually use logging throughout its own code. Then, types from java.logging appear in many places independent of Driver and can no longer be considered to be limited to the boundary of our module and java.sql.

A similar juxtaposition can be created for our advent calendar: Does the main module advent, which requires advent.calendar, only use advent.surprise for the surprise factories that it needs to create the calendar? Or does it have a use for the surprise module independently of its interaction with the calendar?

A module should be explicitly required if it is used on more than just the boundary to another module.

With Jigsaw being cutting edge, the community still has time to discuss such topics and agree on recommended practices. My take is that if a module is used on more than just the boundary to another module, it should be explicitly required. This approach clarifies the system’s structure and also future-proofs the module declaration for various refactorings.

Aggregation And Decomposition

Implied readability enables some interesting techniques. They rely on the fact that with it a client can consume various modules’ APIs without explicitly depending on them if it instead depends on a module that publicly requires the used ones.

Aggregator modules bundle the functionality of related modules into a single unit.

One technique is the creation of so-called aggregator modules, which contain no code on their own but aggregate a number of other APIs for easier consumption. This is already being employed by the Jigsaw JDK, which models compact profiles as modules that simply expose the very modules whose packages are part of the profile.

Another is, what Alex Buckley calls downward decomposability: A module can be decomposed into more specialized modules without compatibility implications if it turns into an aggregator for the new modules.

But creating aggregator modules brings clients into the situation where they internally use APIs of modules on which they don’t explicitly depend. This can be seen as conflicting with what we said above, i.e. that implied readability should only be used on the boundary to other modules. But I think the situation is subtly different here.

Aggregator modules have a specific responsibility: to bundle the functionality of related modules into a single unit. Modifying the bundle’s content is a pivotal change. “Regular” implied readability, on the other hand, will often manifest between not immediately related modules (as with java.sql and java.logging), where the implied module is used more incidentally.

This is somewhat similar to the distinction between composition and aggregation but (a) it’s different and (b), lamentably, aggregator modules would be more on the side of composition. I’m happy to hear ideas on how to precisely express the difference.

Reflection

We have seen how implied readability can be used to make a module’s public API immediately usable, even if it contains types from another module. It enables aggregator modules and downwards decomposability.

We discussed how far we should take implied readability and I opined that a module should only lean on implied readability if it merely uses the implied module’s API on the boundary to a module it explicitly depends on. This does not touch on aggregator module as they use the mechanism for a different purpose.

| Reference: | Implied Readability from our JCG partner Nicolai Parlog at the CodeFx blog. |