Agile Lifecycles for Geographically Distributed Teams

Most of them start this way: someone takes a Scrum class, gets all excited. This is good. Then reality hits. Scrum is meant for collocated geographically cross-functional teams. Uh oh.

Almost all of these teams are separated by function: the developers are in one place, the testers are in another, the business analysts are in a third place, the project managers are in a fourth places, and if there are product owners (or what passes for product owners) they are often in a fifth location. It’s not uncommon for every single function of the team to be separate from every other member of the team. So, the teams don’t fit the Scrum criteria. Uh oh.

Since Scrum has so much brand recognition, these people think if they can’t do Scrum, they can’t do Agile. Nope, not so. What they need to do is start from the values and principles of the Agile Manifesto, and go from there. They create their own lifecycle, and their very own brand of Agile.

When I worked with one client, that client thought they could extend their iteration. Nope, if anything, that means you keep the iterations even shorter, because you need more frequent feedback when no one is in the same place. Well, there were words. And more words. But, if you start from the values, you see that short iterations are the way to go if you want to be agile. Otherwise, you get staged delivery, which is a lovely lifecycle, but not agile.

I’m blogging a series of examples. Please don’t ask me why the people ended up in these locations. I have no idea. All I know is that’s where the people are.

Example 1: Using a Project Manager With Iterations, Silo’d Teams

One IT organization has teams with developers in the Ukraine, testers in India, product managers and project managers in the UK, and enterprise architecture and corporate management in the eastern US.

This organization moved to two-week iterations. The developers were 3.5 hours ahead of the testers, which was not terrible. This organization had these problems:

- The product managers had to learn to be product owners and write stories that were small enough to finish inside one iteration.

- The enterprise architects had to stop dictating the architecture without features to hang off the architecture.

- The developers and testers had to learn to implement by feature so the architects could help the team see the evolving architecture.

This organization had a ton of command-and-control to start. The project managers needed to facilitate the teams, not control them. The architects needed to help the teams see how to organize the product, not to tell the developers what to do. The testers needed to not be order-takers, as in taking orders from the developers.

You might ask why the organization wanted to move to agile. Senior management wanted agile because the releases got longer and longer and longer, and could not accommodate change. Agile was a complete cultural shift. The two-week iterations, along with an agile roadmap of features helped a lot.

The pilot project team consisted of the developers, testers, a product manager, and a project manager. The team rejected the enterprise architect as a member of the team because the architect refused to write code.

Release planning: The project manager and the product manager do an initial cut at release planning as a strawman and presented it to the team. “Can you do this? What do you think?”

Iteration planning: The team does iteration planning together, making sure every story is either small, medium, or large, where a large story can be done by the entire team in fewer than three days. The team makes sure they get every started story to done at the end of the iteration.

Daily commitment: The team does a daily checkin, not a standup. They timebox the checkin to 15 minutes. They ask these questions:

- What did you complete and with whom yesterday? (reinforces the idea that people work together)

- What are you working on and with whom today?

- What are your impediments?

The project manager who acts as a servant leader, not a command/controller manages the impediments.

The pilot project has two experienced agile people: the project manager and a developer. Both act as servant leaders.

Measurements: burnup charts, impediment charts

The pilot team has been together for six months now, and is successful. This is not Scrum. It’s not Kanban. It’s agile and it’s working. They are ready to start another project team, working by attraction.

Example 2: Using a Project Manager with Kanban, Silo’d Teams

This is a product development organization with developers in Italy, testers in India, more developers in New York, product owners and project managers in California.

This organization first tried iterations, but the team could never get to done. The problem was that the stories were too large. Normally I suggest smaller iterations, but one of the developers suggested they move to kanban.

The New York developers had a problem biting off more than they could chew. So nothing moved across their board. The Italy developers had a board where the work did move across the board. The teams took pictures of their boards every day and shared the work across a project-based wiki. That allowed the New York-based developers to see the work move across the Italy board. And, that encouraged the New Yorkers to call the Italians and ask some questions. That helped the New Yorkers to change the size of their work by working with the product owners.

Now, why did the New Yorkers have such trouble originally? Because the developers “knew better” than the product owners, so they changed the stories into architectural features when they had originally received them. (Now they don’t. They leave the stories as real stories.)

Release planning: Management in California plan with agile roadmaps. They have features planned specifically week-by-week for the next 6 weeks, and have more of a quarter-by-quarter approach after that.

Iteration planning: No iteration planning because they are using kanban.

Daily commitment: No daily commitment needed because they use kanban. They do have a checkin a few times a week with each other as a technical team to make sure they don’t create bottlenecks and that they respect the WIP (work in progress) limits.

At one point, both the New York and Italy developer teams created automated tests so that the testers could catch up and stay caught up with regression tests. They add a story like that every couple of weeks, and they are paying down their automated testing debt.

The Project manager keeps an eye on the WIP, work in progress. Project manager also shepherds the product owner into keeping the queue of incoming work full and properly ranked. The product owner is notorious for changing the incoming work queue all the time. Project manager makes sure the team does retrospectives and is a little unclear how to do them in such a distributed team. The project manager is not so sure their retrospectives are working, and has started an obstacle list, to make sure the team has transparency for their obstacles.

Measurements: cumulative flow, average time to release a feature into the product.

Example 3: Using a Project Manager with Iterations and Kanban and Silo’d Teams

Here, the developers were in Cambridge, MA, the product owners were in San Francisco, the testers were in Bangalore, and the project manager was always flying somewhere, because the project manager was shared among several projects. The developers knew about timeboxed iterations, so they used timeboxes. Senior management had made the decision to fire all the local testers and buy cheaper tester time over the developers’ objections and move the testing to Bangalore. The Indian testers were very smart, and unfamiliar with the product, so the developers suggested the testers test feature by feature inside the iteration.

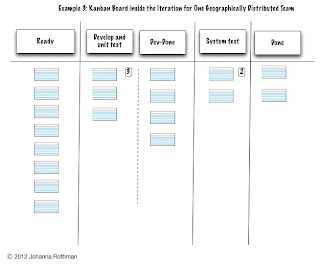

The project manager suggested they use cumulative flow diagrams and cycle time measurements to make sure the developers were not developing “too fast” for the testers. The developers, still smarting over the loss of “their testers” were at first, peeved about this. They then realized the truth of this statement, and developed this kanban board.

You can see in this board, that four items are waiting to go into system test. Uh oh. The developers are out-producing what the testers can take. This is precisely what a kanban board can show you.

The testers aren’t stupid or slow. They are new. They cannot keep up with the developers. It’s a fact of life, not a mystery of life. The developers have to act in some way to help the testers or the entire project will fail. The reason they are working in timeboxes as well as using kanban is that they have several contractual deliverables, that management, bless their tiny little hearts, committed to. The timebox allows the team or the product owners to meet with their customers and show them their progress. (They were deciding who would meet when I last worked with the team.) The kanban board help make the progress even more transparent.

Iteration planning: The product owner and the project manager jointly work on the agile feature roadmap, and the product owner owns the roadmap responsibility for it. The product owner owns and generates the backlog. The product owner and the agile project manager present a strawman iteration backlog to the team at the start of the iteration. They have had difficulty finding iteration planning time that allows everyone to be awake and functioning, bless the senior managers’ little hearts.

Daily commitment: They do a handoff, asking each other what they completed that day and what the impediments are. If you have read Manage It!, you know I modified the three questions to “What did you complete, what are you planning to complete, what is in your way?”

Measurements: cumulative flow, average time to release a feature into the product. They are experimenting with burnup charts and impediment charts. They are still having trouble bringing the testers up to speed fast enough.

Yes, they do retrospectives at the end of each iteration. Yes, the product owners own the backlogs.

I’ll summarize in the final part, the next entry.

(Want to learn to work more effectively on your geographically distributed team? Join Shane Hastie and me in a workshop April 17-18, 2012.)

Reference: Agile Lifecycles for Geographically Distributed Teams, Part 1, Agile Lifecycles for Geographically Distributed Teams, Part 2 & Agile Lifecycles for Geographically Distributed Teams, Part 3 from our JCG partner Johanna Rothman at the Managing Product Development blog.