Service Discovery: Zookeeper vs etcd vs Consul

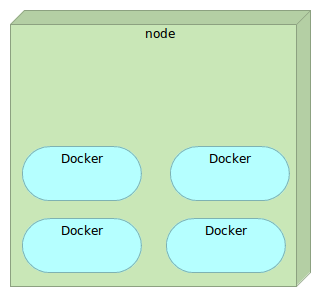

The more services we have, the bigger the chance for a conflict to occur if we are using predefined ports. After all, there can be no two services listening on the same port. Managing a tight list of all the ports used by, lets say, hundred services is a challenge in itself. Add to that list the databases those services need and the number grows even more. For that reason we should deploy services without specifying the port and letting Docker assign a random one for us. The only problem is that we need to discover the port number and let others know about it.

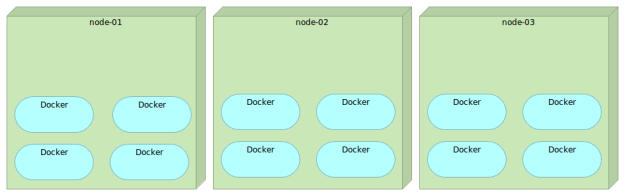

Things are getting even more complicated when we start working on a distributed system with services deployed into one of the multiple servers. We can choose to define in advance which service goes to which server but that would cause a lot of problems. We should try to utilize server resources as best we can and that is hardly possible if we define in advance where to deploy each service. Another problem is that automatic scaling of services would be difficult at best and not to mention automatic recuperation from, let’s say, server failure. On the other hand, if we deploy services to the server that has, for example, least number of containers running, we need to add the IP to the list of data needed to be discovered and stored somewhere.

There are many other examples of cases when we need to store and retrieve (discover) some information related to the services we are working with.

In order to be able to locate our services we need at least the following two processes to be available for us.

- Service registration process that will store, as a minimum, the host and the port service is running on.

- Service discovery process that will allow others to be able to discover the information we stored during the registration process.

Besides those processes, we need to consider several other aspects. Should we unregister the service if it stops working and deploy/register a new instance? What happens when there are multiple copies of the same service? How do we balance the load among them? What happens if a server goes down? Those and many other questions are tightly related to the registration and discovery processes. For now, we’ll limit the scope only to the service discovery (common name that envelops both aforementioned processes) and the tools we might use for such a task. Most of them feature some kind of highly available distributed key/value storage.

Service discovery tools

The main objective of service discovery tools is to help services find and talk to one another. In order to perform their duty they need to know where each service is. The concept is not new and many tools existed long before Docker was born. However, containers brought the need for such tools to a completely new level.

The basic idea behind service discovery is for each new instance of a service (or an application) to be able to identify its current environment and store that information. Storage itself is performed in a registry usually in key/value format. Since the discovery is often used in distributed system, registry needs to be scalable, fault tolerant and distributed among all nodes in the cluster. Primary usage of such a storage is to provide, as a minimum, IP and port of the service to all interested parties that might need to communicate with it. This data is often extended with other types of information.

Discovery tools tend to provide some kind of API that can be used by a service to register itself as well as by others to find the information about that service.

Let’s say that we have two services. One is a provider and the other one is its consumer. Once we deploy the provider we need to store its information to the service discovery registry of choice. Later on, when the consumer tries to access the provider, it would first query the registry and call the provider using the IP and port obtained from the registry. In order to decouple the provider from the specific implementation of the registry, we often employ some kind of proxy service. That way the consumer would always request information from the fixed address that would reside inside the proxy that, in turn, would use the discovery service to find out the provider information and redirect the request. We’ll go through reverse proxy later on in the book. For now it is important to understand the flow that is based on three actors; consumer, proxy and provider.

What we are looking for in the service discovery tools is data. As a minimum we should be able to find out where the service is, whether it is healthy and available and what is its configuration. Since we are building a distributed system with multiple servers, the tool needs to be robust and failure of one node should not jeopardize data. Also, each of the nodes should have exactly the same data replica. Further on, we want to be able to start services in any order, be able to destroy them or replace them with newer versions. We should also be able to reconfigure our services and see the data change accordingly.

Let’s take a look at few of the commonly used options to accomplish the goals we set.

Manual configuration

Most of the services are still managed manually. We decide in advance where to deploy the service, what is its configuration and hope beyond reason that it will continue working properly until the end of days. Such approach is not easily scalable. Deploying a second instance of the service means that we need to start the manual process all over. We need to bring up a new server or find out which one has low utilization of resources, create a new set of configurations and deploy it. The situation is even more complicated in case of, let’s say, a hardware failure since the reaction time is usually slow when things are managed manually. Visibility is another painful point. We know what the static configuration is. After all, we prepared it in advance. However, most of the services have a lot of information generated dynamically. That information is not easily visible. There is no single location we can consult when we are in need of that data.

Reaction time is inevitably slow, failure resilience questionable at best and monitoring difficult to manage due to a lot of manually handled moving parts.

While there was excuse to do this job manually in the past or when the number of services and/or servers is low, with emergence of service discovery tools, this excuse quickly evaporates.

Zookeeper

ZooKeeper is one of the oldest projects of this type. It originated out of the Hadoop world, where it was built to help in the maintenance of the various components in a Hadoop cluster. It is mature, reliable and used by many big companies (YouTube, eBay, Yahoo, and so on). The format of the data it stores is similar to the organization of the file system. If run on a server cluster, Zookeper will share the state of the configuration across all of nodes. Each cluster elects a leader and clients can connect to any of the servers to retrieve data.

The main advantages Zookeeper brings to the table is its maturity, robustness and feature richness. However, it comes with its own set of disadvantages as well, with Java and complexity being main culprits. While Java is great for many use cases, it is very heavy for this type of work. Zookeeper’s usage of Java together with a considerable number of dependencies makes it much more resource hungry that its competition. On top of those problems, Zookeeper is complex. Maintaining it requires considerably more knowledge than we should expect from an application of this type. This is the part where feature richness converts itself from an advantage to a liability. The more features an application has, the bigger the chances that we won’t need all of them. Thus, we end up paying the price in form of complexity for something we do not fully need.

Zookeeper paved the way that others followed with considerable improvements. “Big players” are using it because there were no better alternatives at the time. Today, Zookeeper it shows its age and we are better off with alternatives.

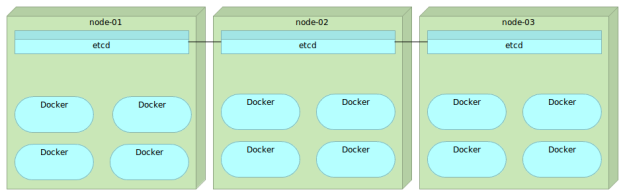

etcd

etcd is a key/value store accessible through HTTP. It is distributed and features hierarchical configuration system that can be used to build service discovery. It is very easy to deploy, setup and use, provides reliable data persistence, it’s secure and with a very good documentation.

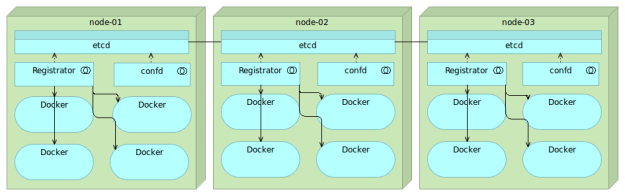

etcd is a better option than Zookeeper due to its simplicity. However, it needs to be combined with few third-party tools before it can serve service discovery objectives.

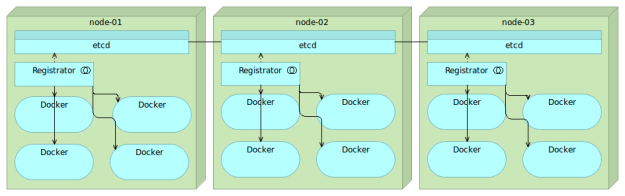

Now that we have a place to store the information related to our services, we need a tool that will send that information to etcd automatically. After all, why would we put data to etcd manually if that can be done automatically. Even if we would want to manually put the information to etcd, we often don’t know what that information is. Remember, services might be deployed to a server with least containers running and it might have a random port assigned. Ideally, that tool should monitor Docker on all nodes and update etcd whenever a new container is run or an existing one is stopped. One of the tools that can help us with this goal is Registrator.

Registrator

Registrator automatically registers and deregisters services by inspecting containers as they are brought online or stopped. It currently supports etcd, Consul and SkyDNS 2.

Registrator combined with etcd is a powerful, yet simple combination that allows us to practice many advanced techniques. Whenever we bring up a container, all the data will be stored in etcd and propagated to all nodes in the cluster. What we’ll do with that information is up to us.

There is one more piece of the puzzle missing. We need a way to create configuration files with data stored in etcd as well as run some commands when those files are created.

confd

confd is a lightweight configuration management tool. Common usages are keeping configuration files up-to-date using data stored in etcd, consul and few other data registries. It can also be used to reload applications when configuration files change. In other words, we can use it as a way to reconfigure all the services with the information stored in etcd (or many other registries).

Final thoughts on etcd, Registrator and confd combination

When etcd, Registrator and confd are combined we get a simple yet powerful way to automate all our service discovery and configuration needs. This combination also demonstrates effectiveness of having the right combination of “small” tools. Those three do exactly what we need them to do. Less than this and we would not be able to accomplish the goals set in front of us. If, on the other hand, they were designed with bigger scope in mind, we would introduce unnecessary complexity and overhead on server resources.

Before we make the final verdict, let’s take a look at another combination of tools with similar goals. After all, we should never settle for some solution without investigating alternatives.

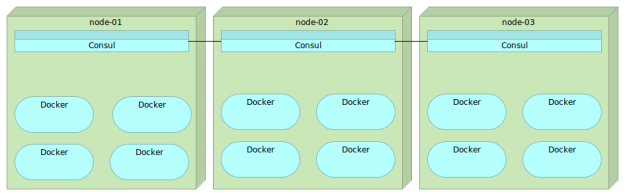

Consul

Consul is strongly consistent datastore that uses gossip to form dynamic clusters. It features hierarchical key/value store that can be used not only to store data but also to register watches that can be used for a variety of tasks from sending notifications about data changes to running health checks and custom commands depending on their output.

Unlike Zookeeper and etcd, Consul implements service discovery system embedded so there is no need to build your own or use a third-party one. This discovery includes, among other things, health checks of nodes and services running on top of them.

ZooKeeper and etcd provide only a primitive K/V store and require that application developers build their own system to provide service discovery. Consul, on the other hand, provides a built in framework for service discovery. Clients only need to register services and perform discovery using the DNS or HTTP interface. The other two tools require either a hand-made solution or the usage of third-party tools.

Consul offers out of the box native support for multiple datacenters and the gossip system that works not only among nodes in the same cluster but across datacenters as well.

Consul has another nice feature that distinguishes it from the others. Not only that it can be used to discover information about deployed services and nodes they reside on, but it also provides easy to extend health checks through HTTP requests, TTLs (time-to-live) and custom commands.

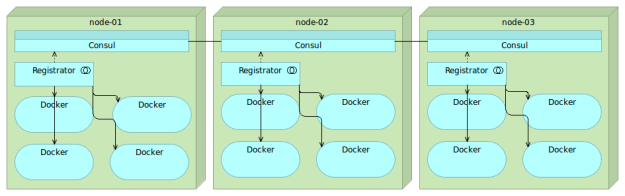

Registrator

Registrator has two Consul protocols. The consulkv protocol produces similar results as those obtained with the etcd protocol.

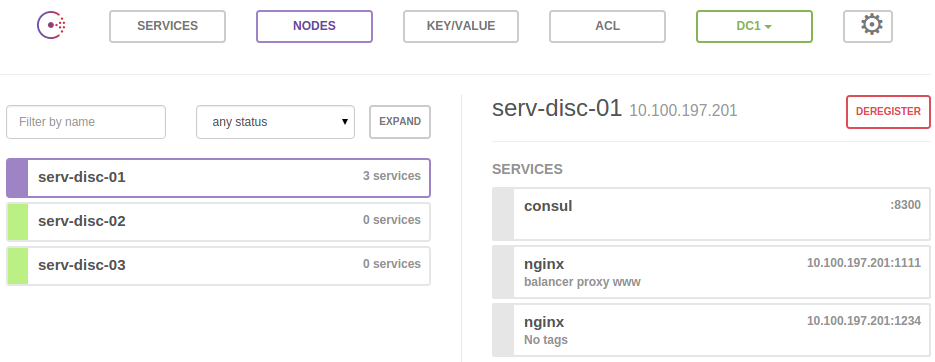

Besides the IP and the port that is normally stored with etcd or consulkv protocols, Registrator’s consul protocol stored more information. We get the information about the node the service is running on as well as service ID and name. With few additional environment variables we can also store additional information in form of tags

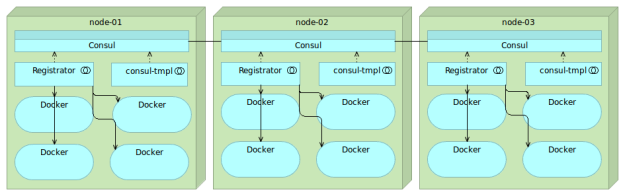

consul-template

confd can be used with Consul in the same way as with etcd. However, Consul has its own templating service with features more in line with what Consul offers.

The consul-template is a very convenient way to create files with values obtained from Consul. As an added bonus it can also run arbitrary commands after the files have been updated. Just as confd, consul-template also uses Go Template format.

Consul health checks, Web UI and datacenters

Monitoring health of cluster nodes and services is as important as testing and deployment itself. While we should aim towards having stable environments that never fail, we should also acknowledge that unexpected failures happen and be prepared to act accordingly. We can, for example, monitor memory usage and if it reaches certain threshold move some services to a different node in the cluster. That would be an example of preventive actions performed before the “disaster” would happen. On the other hand, not all potential failures can be detected on time for us to act on time. A single service can fail. A whole node can stop working due to a hardware failure. In such cases we should be prepared to act as fast as possible by, for example, replacing a node with a new one and moving failed services. Consul has a simple, elegant and, yet powerful way to perform health checks and help us to define what actions should be performed when health thresholds are reached.

If you googled “etcd ui” or “etcd dashboard” you probably saw that there are a few solutions available and might be asking why we haven’t presented them. The reason is simple; etcd is a key/value store and not much more. Having an UI to present data is not of much use since we can easily obtain it through the etcdctl. That does not mean that etcd UI is of no use but that it does not make much difference due to its limited scope.

Consul is much more than a simple key/value store. As we’ve already seen, besides storing simple key/value pairs, it has a notion of a service together with data that belongs to it. It can also perform health checks thus becoming a good candidate for a dashboard that can be used to see the status of our nodes and services running on top of them. Finally, it understands the concept of multiple datacenters. All those features combined let us see the need for a dashboard in a different light.

With the Consul Web UI we can view all services and nodes, monitor health checks and their statuses, read and set key/value data as well as switch from one datacenter to another.

Final thoughts on Consul, Registrator, Template, health checks and Web UI

Consul together with the tools we explored is in many cases a better solution than what etcd offers. It was designed with services architecture and discovery in mind. It is simple, yet powerful. It provides a complete solution without sacrificing simplicity and, in many cases, it is the best tool for service discovery and health checking needs.

Conclusion

All of the tools are based on similar principles and architecture. They run on nodes, require quorum to operate and are strongly consistent. They all provide some form of key/value storage.

Zookeeper is the oldest of the three and the age shows in its complexity, utilization of resources and goals it’s trying to accomplish. It was designed in a different age than the rest of the tools we evaluated (even though it’s not much older).

etcd with Registrator and confd is a very simple yet very powerful combination that can solve most, if not all, of our service discovery needs. It also showcases the power we can obtain when we combine simple and very specific tools. Each of them performs a very specific task, communicates through well established API and is capable of working with relative autonomy. They themselves are microservices both in their architectural as well as functional approach.

What distinguishes Consul is the support for multiple datacenters and health checking without the usage of third-party tools. That does not mean that the usage of third-party tools is bad. Actually, throughout this blog we are trying to combine different tools by choosing those that are performing better than others without introducing unnecessary features overhead. The best results are obtained when we use right tools for the job. If the tool does more than the job we require, its efficiency drops. On the other hand, tool that doesn’t do what we need it to do is useless. Consul strikes the right balance. It does very few things and it does them well.

The way Consul propagates knowledge about the cluster using gossip makes it easier to set up than etcd especially in case of a big datacenter. The ability to store data as a service makes it more complete and useful than key/value storage featured in etcd (even though Consul has that option as well). While we could accomplish the same by inserting multiple keys in etcd, Consul’s service accomplishes a more compact result that often requires a single query to retrieve all the data related to the service. On top of that, Registrator has quite good implementation of the consul protocol making the two an excellent combination, especially when consul-template is added to this picture. Consul’s Web UI is like a cherry on top of a cake and provides a good way to visualize your services and their health.

I can’t say that Consul is a clear winner. Instead, it has a slight edge when compared with etcd. Service discovery as a concept as well as the tools we can use are so new that we can expect a lot of changes in this field. Have an open mind and try to take advises from this article with a grain of salt. Try different tools and make your own conclusions.

| Reference: | Service Discovery: Zookeeper vs etcd vs Consul from our JCG partner Viktor Farcic at the Technology conversations blog. |