Impulse: “Crafted Design”

About half a year ago I urged you to watch Robert C. Martin’s talk Architecture – The Lost Years. It argued in favor of a design that clearly displays the application’s domain (e.g. logical units, services, use cases, …) and keeps auxiliary aspects (e.g. delivery mechanism, persistence, …) on the sidelines.

While I really liked the talk, it was fairly theoretical (which isn’t a bad thing). Now I found the perfect counterpart: Crafted Design by Sandro Mancuso. His problem statement is essentially the same and so are the central concepts of his solution. But his talk is far more practical and filled with concrete examples.

You should watch it!

Overview

As usual for this series of posts, I won’t reproduce the whole talk. Here I will focus on the described architecture, leaving out most of the motivation and the thought process that led to that approach as well as interesting connected topics like how to test such a system.

This gives me the opportunity to fill the hole that I left in my post about Martin’s talk, where I did it the other way around.

The Talk

https://vimeo.com/101106002

The slides are up on slideshare. Any diagrams which appear in this post are taken from those slides.

A Little Bit Of Motivation

Just to make sure we’re all on the same page (even if you didn’t go back and watch Martin’s talk or read my post), I will quickly summarize the motivation.

The Goal

When you look into a project’s package structure, you should immediately be able to see the following:

- What is the application about? What are the main concepts?

- What does the application do? What are the main features?

- Where do I need to change? Where do I put a new feature?

More often, though, you see controllers, repositories, helpers, … or an arbitrary structure according to some functional relationships. In any way, nothing related to the domain.

Model-View-Controller

A frequent source of this is that the delivery mechanism (e.g. a web UI or REST interface) defines the structure.

For example, with MVC many opinionated frameworks (or just developers’ habits) organize source code according to the pattern. This leads to a code structure which does not at all reflect the application’s domain.

Mancuso goes on to discuss some more problems coming from overusing MVC as a basic structure for a project.

What does it do? I have no idea.

But it’s a web app! That’s the important thing!

The Crafted Design

There should be a clear distinction between the delivery mechanism and the domain. The former might very well employ MVC, where view and controller are whatever the framework requires them to be. But the model must be a self-sufficient representation of the domain.

And this model is the focus of the rest of the talk.

The Model In Domain-Driven Design

The model would be the domain model as defined in domain-driven design. It contains the domain’s state (mainly in the form of entities) and behavior (in the form of different services).

Any infrastructure required by the model is also implemented here. But it is recognizable as such and not mixed with domain concepts to keep the model undiluted. (E.g. “Send-An-E-Mail” is a service but it’s implementation is infrastructure.)

This makes the model a runnable, self contained solution for the problem the application is built for.

Responsibilities

The responsibilities of the different parts of the system are well-defined:

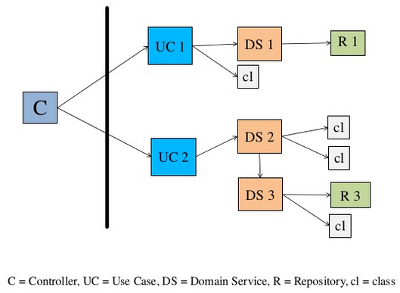

Controllers

Controllers exist outside of the model and may interact with it via different mechanisms (e.g. REST). When they need something to happen, they call a use case (or sometimes more than one).

Use Cases

Use cases describe the actions that the application performs (e.g. “create an author”). They are exposed to the outside world and are the entry point into the domain model.

Domain Services

A domain service is related to one domain concept (e.g. “authors” or “books”), to which it is the entry point. To fulfill its task, the service may talk to other services.

Infrastructure Services, Repositories, …

All other instances are bound to one domain concept and never exposed to the outside world. The only exception are the domain entities which are used throughout the whole domain.

This implies that, e.g., a domain service for authors will never talk to the books repository to fetch some books; it would instead call the “fetch books service”.

Infrastructure Implementations

While interfaces of infrastructure services, repositories and the like are part of the domain model, their implementations are often considered to be infrastructure.

So while the “Authorize-User-Service” is defined as an infrastructure service in the domain model, it’s implementation, e.g. for OAuth, will be found among other infrastructure implementations.

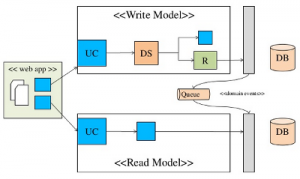

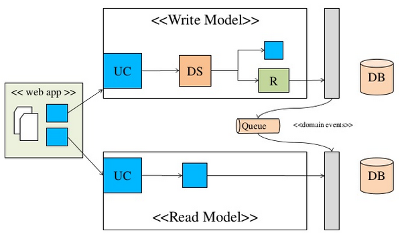

Use cases and services should be built considering command query responsibility segregation. Here, individual instances are either responsible for executing a command or for querying and returning information.

Names

Quick detour on names… Mancuso says he tries as much as he can to avoid using architectural concepts as names.

So e.g. for repositories instead of UserRepository or BookRepository he would pick Users or Library, respectively.

Repositories

Repositories are similar to data access objects. But while the former are more data centric and expose CRUD operations, the latter appear as a collection with useful query methods.

According to the responsibilities discussed above, entities and repositories are separated by domain concepts. This helps when working with a complex domain model, which is usually represented by a similarly complex and intertwined entity graph. Problems often come from different queries which have very different needs (e.g. what should be loaded, whether lazy-loading should be used, pagination, …) but are mapped to the same fixed entity graph. The presented approach splits the relationships apart so that no entity references other ones from a different concept.

This is mostly sufficient for writing to the database, where it is very common to only deal with one concept at a time (e.g. “insert comment” or “update rating”). Such commands can hence be managed by a single use case in coordination with a domain service and the involved entity.

But it is more complicated for reading from the database where it is often required to combine the information from different domain concepts. Instead of going through the domain model and trying to put all the requested entities together, Mancuso recommends to use a customized query which creates a denormalized object with exactly the right data. This makes the code very expressive (because the query and the object representing the result just exist for this single use case) and keeps the domain model clean. He calls this a fast track.

Structure

With this the project’s modules/source-folders/packages (depending on what you’re doing) can be structured as follows:

Core

Self-contained solution to the problem the application was built for.

Infrastructure

The infrastructure required for the model.

Model

The domain model, i.e. all the entities and services.

Use Cases

The use cases in individual classes.

Delivery

Contains whatever the project uses to be delivered, e.g. the desktop UI or the web integration. This part of the project can be structured according to the framework’s needs.

The slides contain more screenshots of actual folder structures (from slide 22 on).

Core

The content of the folder model clearly shows what the application is about – names will usually consist of nouns. The folder will typically have subfolders (e.g. book) which will contain all classes related to a domain concept (entities, services, repositories; remember not the infrastructure).

The content of use cases plainly shows what the application does – names will usually consist of verbs. The use cases may be organized into subfolders which may relate to epics or user stories.

The infrastructure will contain “all the external stuff”, which is not part of the domain. These classes will usually implement interfaces defined in the model.

Delivery

With this structure typical problems of MVC can be solved. For example the controllers do no longer contain business logic. Instead they only do what they were meant to do: control flow. They take a query from the view, call the correct use case, take the returned data and use it to update the view. All this is a couple of lines so no more fat controllers.

Flow From Abstract To Specific

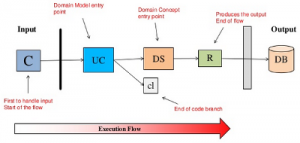

After describing this architectural approach, Mancuso makes an observation about the flow from abstract to specific behavior.

All interaction starts with some input for the use cases. They delegate to services, which reach into the domain to modify or query the entities or create some output. So while the instances closer to the input are mainly tasked with controlling the flow, the ones closer to the output are performing the actual work. At the same time the former are employing a higher level of abstraction while the latter implement very specific behavior.

In the diagram on the right this means a control flow from left (input) to right (output). The further to the left, the more abstract the concepts and the more flow control is exercised. The closer to the right, the less abstract are the concepts and the more concrete is the behavior.

Tests & More

There are substantial parts of the talk, which I do not cover.

One explains how different styles of testing can be used to verify the behavior of different parts of the system. If this interests you, check it out! (It starts at 29:53.)

Also, Mancuso was cutting through his slides like a hot knife through butter so there are almost twenty minutes of questions. They are about security, modularization, event sourcing and more with interesting answers. Again: check it out! (Starts at 36:57.)

Reflection

We have seen how a crafted design can structure a code base into modules/folders/packages which plainly show the application’s main concepts and features.

To achieve this, domain-driven design should be employed to create domain entities and services (the concepts). Use cases (the features) are implemented as individual classes. They are the entry point into the system and orchestrate its behavior.

The project core’s top level folder should then contain these two subfolders along with one for the infrastructure implementation (which is separated to keep the domain model clean).

The delivery mechanism, be it a rich desktop UI, a web UI and/or a REST interface, should be isolated into its own project/module/folder. It can be organized according to whatever structure fits best. But is important to keep its controllers slim! They should never do more than call one, maybe two use cases and update the view according to the calls’ results.

| Reference: | Impulse: “Crafted Design” from our JCG partner Nicolai Parlog at the CodeFx blog. |